Topic:

Farming practices at Mount Elgin Residential School

What’s new:

There is evidence in Mount Elgin’s records obtained through an access to information request that children were forced to labour on the farm. An RCMP report says that students ran away from the school and often complained that the conditions were too hard on them.

Why it’s important:

Little has been published on Mount Elgin, which operated just outside of London until 1946. It was mentioned briefly in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 2015 reports as one of the few schools that operated in southern Ontario.

The records show how the school operated, and how children were used to benefit the farm.

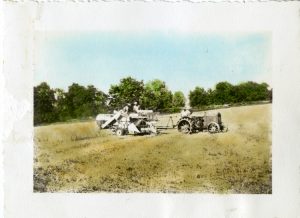

In 1945, the school farmed hundreds of bushels of crops.

As noted in the above document, the school only employed one farmer, so the students were left doing most of the work.

Anne Lindsay, an archivist from the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, noted that it was common for residential schools in Ontario to run farms for the students to learn how to harvest crops and to subsidize some of the costs for food.

An RCMP report from 1943 shows the repercussions and impacts of these extreme farming practices at Mount Elgin. Constable W.E. Needham was called to retrieve students who had run away from the school. In the report, the officer explains that the students ran away because they were forced to work on the farm. The officer calls the discipline “too severe.”

“[These] children have very little or no recreation,” wrote Needham in the report, “and with help so scarce they are obliged to do the majority of the farm work, resulting in these children being overworked.”

That children ran away from residential schools is not new information. What is new information is that many were running away from Mount Elgin because they were being overworked on the farm.

In the grander scheme of things, this report shows that new information is still coming to the surface about what happened in these schools. Though the offices of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission have closed and become the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the process of reconciling with the past is not over because new information is still being discovered.

What the government says:

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada could not comment on this school in particular. The spokesperson simply referred to the webpage on reconciliation when asked what the government does when new information surfaces about the operation of schools, whether that changes the reconciliation process.

Lindsay at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation was quick to dismiss the report and its implications.

“At that time, children were an economic part of a family,” said Lindsay. “You have to look at it in the context of childhood at that time.”

What others say:

Mike Cachagee is the president of the Ontario Indian Residential School Support Services. He is from Chapleau Cree First Nation and is a residential school survivor. Though he never went to Mount Elgin, he was one of the student farm hands at residential schools near Thunder Bay.

Cachagee did not agree with Lindsay’s assessment of the report.

“If they had done the same thing with white schools, yes I could say this was a sign of the times, but they didn’t,” said Cachagee. “It was a sign of the times in how they treated Indigenous people.”

What’s next:

Indigenous groups like Ontario Indian Residential School Support Services are working with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation to ensure accurate recording of what occurred at residential schools across the country. As more reports are found and filed, new information is surfacing about what went on at these schools. According to Cachagee, the Ontario Indian Residential School Services want to make sure that information is properly archived and used for educating the public.

Documents: