George Fry boarded a ship destined for Liverpool in the late summer of 1907. He had arrived in Alberta only a few months earlier. Red Deer, where he found work, was booming. The town had just become a divisional point for the Canadian Pacific Railway and was bracing for a wave of settlers. Fry, a bricklayer in his forties, wouldn’t be there to see it.

Fry had contracted syphilis more than fourteen years earlier and was facing deportation, according to archival material available online. The discovery of penicillin was still decades away, and Fry’s infection could have already spread to his internal organs and brain.

“George Fry is suffering from syphilitis and dangerous to be at large. Do not delay deporting,” his immigration records warned.

Newcomers to Canada still face medical scrutiny today. However, a system overhaul could be coming. Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen says he plans to announce changes to Canada’s medical inadmissibility policy in April, after calling it “out of step with Canadian values.”

The current policy allows the government to deny residency to people whose medical conditions could place excessive demand on Canada’s health care system. Advocates say it discriminates against people with disabilities.

Fry’s fate might have been different had he arrived in Canada a year earlier. The Immigration Act of 1906 tightened restrictions on prohibited immigrants. Under the new act, any immigrant who was “feeble-minded, an idiot, or an epileptic, or who is insane” was considered undesirable.

The physically unwell were also prohibited, including those “afflicted with a loathsome disease… which may become dangerous to the public health or widely disseminated.”

The immigrant’s journey itself was a source of sickness. Canadian port officers became used to dealing with immigrants who fell ill during their lengthy voyage on a crowded ship.

As legislation stiffened, the focus of medical examination shifted from immediate contagion to overall fitness. For Lisa Chilton, immigration historian at the University of Prince Edward Island, this change coincided with a growing interest in eugenics.

“Their sense of what was genetic included a lot of things that now a lot of us would say are more class based,” Chilton explained. She cited the once popular argument that African immigrants were genetically incapable of withstanding the Canadian winter.

“Certainly, a lot of the economic arguments were tinged with racism,” Chilton said.

George Fry was born in Wells, England with light brown hair and a medium complexion. He likely wouldn’t have faced the racism that Asian, African, and Irish immigrants did. However, his “loathsome disease” attracted a unique set of prejudices.

“The defectives of other countries are not merely a burden, whether able to be at large or requiring detention, but they are apt to perpetuate a criminal or otherwise defective population,” a Globe and Mail columnist argued in 1910.

Chilton believes that our mentality towards people with disabilities has changed significantly since George Fry’s time.

“There are opportunities to be inclusive in the workplace of people who in the early 20th century would have been seen as just a burden,” she said.

Fry was one of 2,296 immigrants deported for medical reasons between 1902 and 1913. The Immigration Act of 1906 made it easier to deport any immigrant who became a burden to society within two years of their arrival – a sort of probation period.

Fry was deported just five months after he arrived. On Aug. 30, 1907, he boarded the SS Lake Erie bound for Liverpool. A Canadian immigration officer overseas confirmed his arrival ten days later. He was said to be heading to London – returning to the wife he had left behind.

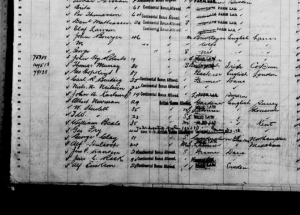

Document 2: Statement regarding George Fry, Department of the Interior, Immigration Branch

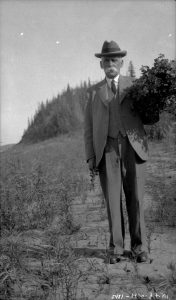

Featured Image: The SS Lake Champlain, on which George Fry first sailed from Liverpool to Quebec. 1911. Credit: Lamb, W.K / Library and Archives Canada / PA-143538.