Jeff Leiper, city Councillor for Kitchissippi Ward, used to be able to see clear down the fence line to the next street over from his backyard. Now, all he sees is brickwork, thanks to a “monster” infill development that’s sprung up in the place of his neighbour’s old 1950s-era home.

“It’s a visual impact,” he says. “All of a sudden, instead of looking at blue sky in that direction, there was this very, very, very large house.”

He’s not alone. As more families move into the city, demand for housing in the downtown core has steadily increased. The increase has spurred an influx of infill development.

“There’s a strong trend towards intensification and gentrification, in which we’re seeing older homes torn down,” says Leiper. “And generally in a lot of our zones they’re replaced with a lot of very large semi-detached homes, so it’s an interesting tension right now.”

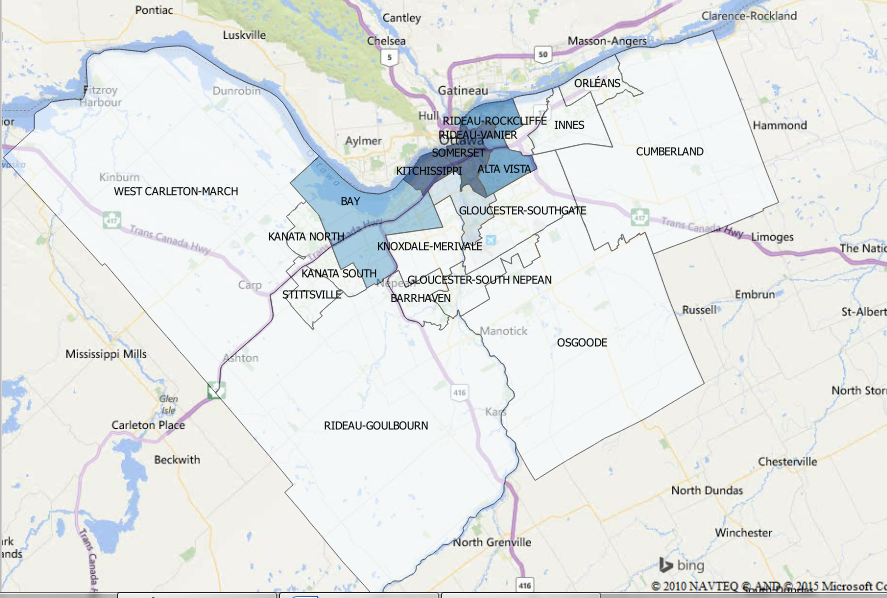

The tension stems from the clash of old versus new in some of Ottawa’s most established communities. According to an analysis of the City of Ottawa’s 2011 ward data from the census and 2011 national household survey, Kitchissippi has the highest number of pre-1960 houses in the city, with nearly 9600 recorded. Rideau-Vanier is a close second with 8400, while Capital ward has 8150.

According to Leiper, these numbers are dropping by the day. “Even just in the last year, it’s been five demolitions every two weeks, or 10 every month that I see,” he says. “It’s hundreds of these infills that have gone in over the last five years.”

The rise in infill development implies a demographic shift as well. Many of the city’s old neighbourhoods were built as inexpensive housing for the working and middle class. “Those of us who bought these smaller homes in the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s; it’s a different demographic from the people who are able to afford these $800,000 and $1.2 million dollar homes,” says Leiper. He says the value of his home has tripled since he bought in 1998.

Marlene Borsboom, a long-time Ottawa real estate agent who now works as a Real Estate Management Officer at the National Capital Commission, says it’s a common situation. “You can have the old, decrepit, worst house that was ever built, but it will sell,” she says. “And usually they sell because someone’s going to buy it and build something else. They can build a detached or semi-detached house, and they can get double the money.”

In an attempt to stem the tide of infill developments, city council passed the Mature Neighbourhoods Bylaw, also known as Infill I. It aims to restrict several aspects of infill development, including front setbacks, parking locations, and balconies. Its partner bylaw, infill II, deals with development outside the core and came into effect this summer. Designated heritage areas and properties also receive special protections.

Infill II

Infill II Bylaw-City of Ottawa-2015-228-July-2015 (Text)

The bylaws are a start, but to Johanna Persohn, Chair of Glebe Community Association’s Heritage Committee, they may not be enough. She’s seen dozens of infill developments in her three years with the association, and says a more concrete zoning and development plan is needed to preserve the character of Ottawa’s older neighbourhoods.

“We’ve had some houses that have literally disappeared overnight, with very little warning,” she says, “and that’s because they fall within the existing zoning on the property and they’re not asking for anything extra.”

However, Persohn maintains infill itself isn’t a bad thing. “If it’s filling in huge, underused lots, that’s a good thing,” she says. “But right now, your developers are only going to teardown to replace with something bigger.”

Ultimately, Persohn is worried that if left unchecked, infill development may begin to have a detrimental impact on the existing character of older neighbourhoods. “These infills can create precedents,” she says. “A lot of them don’t have the same relationship to the street, and it worries me that you could end up in a street full of these and having a completely different feeling.”

According to Kathryn Downey, Supervisor of Health Inspection at Ottawa Public Health,

According to Kathryn Downey, Supervisor of Health Inspection at Ottawa Public Health,