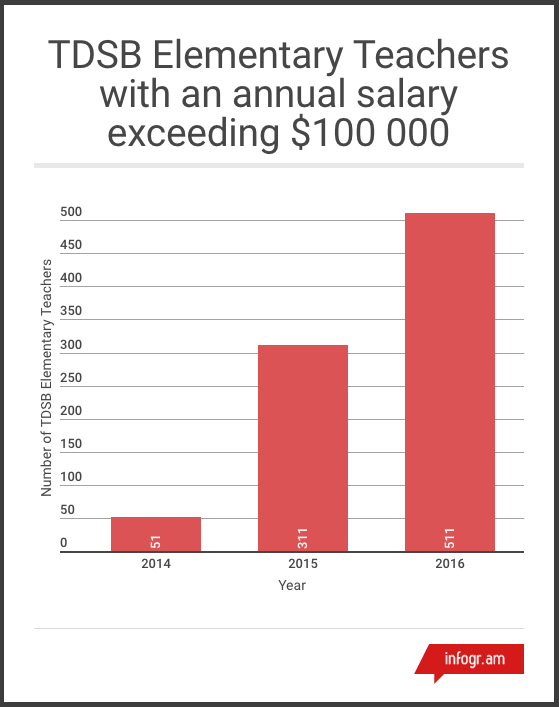

The number of Toronto District School Board teachers with the highest seniority is increasing and so are their bank accounts. Since 2014, seniority has been tied to a 902 per cent increase in elementary teachers who’ve earned an annual salary of over $100 000, according to an analysis of data provided by the provincial government.

The salary data document is informally known as the “sunshine list” is released annually under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act. It lists the salary of public sector employees who earn over $100, 000. In the province’s April 2014 disclosure, 51 Toronto elementary school teachers employed by the public school board made the list. The number jumped to 511 teachers by 2016. Spikes in salaries occurred in elementary school boards across the province but Toronto is home to the largest.

These spikes are despite a collective agreement salary grid which, in 2014, reached $94 707 a year for the highest certified teacher after ten years. It may seem curious that so many teachers have found a way to earn more than union contracts bargained for but a number of factors can tip a teacher’s income above the grid.

Ben Eisen, Director of Fraser Institute’s Provincial Prosperity Studies, said the disparity between the salary grid and what teachers took home in recent years is due to “a combination of taking on additional roles like teaching summer school courses or a becoming a department head coupled with the payout for sick days.”

Many senior level teachers have a Retirement Gratuity account filled with unused sick days. When the practice of collecting unused sick days ended in 2012, several accounts amounted to tens of thousands of dollars but in order to obtain the full value teachers must retire.

Teachers not quite ready to retire can still cash in at a cost of 7.5 per cent for every year short of retirement. When teacher’s contracts expired in August 2014, frantic withdrawals were made to ensure the new provincial majority government didn’t affect their Retirement Gratuity Account.

Ken Lister, Vice Chair of the Financial Budget Committee says the board struggles to bridge the gap between provincial funding and the cost of teachers since their salaries make up two-thirds of their budget. “It’s a historical one,” he says of the funding gap.

The school board’s report, “Financial Facts: Revenue and Expenditure Trends” details the funding gap. “Part of the gap is because we have ‘experienced teachers with seniority’ and labour issues,” said Lister. Lister is not convinced retirement gratuity explains much of the gap. He wants to see the province upload the cost of teacher benefits. “It effects the amount we can spend repairing schools,” he said.

Comparatively, Eisen is concerned what effect compensation is having on the province’s finances and its ability to sustain increasing expenses.

“It’s important to look at in context of the challenges the province is facing, how it fits into the broader fiscal level and high debt level when looking at what’s taking place with respect to compensation,” said Eisen.

There are arguments the disclosure benchmark does not reflect inflation since the act was passed in 1996. According to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator, the benchmark would move to $142,857.14.

According to Eisen, it depends on how the information is used as an accountability measure of the province. “It’s important that additional spending is producing additional results and what’s missing is accountability mechanisms,” said Eisen.

Last February, the teacher’s union was able to secure a two-year extension on the terms of their existing collective bargaining agreement—which includes an annual increase by 1.5 per cent.