Toronto awaits the results of its bid for Amazon HQ2, having surpassed Montreal in the race to house the online retailer’s new headquarters. This incident is a mere update to the longstanding rivalry between Canada’s two largest cities – one which solidifies Toronto’s status as the country’s economic epicentre.

Historically, Montreal was Canada’s longstanding financial and business hub, anchored in the founding of financial institutions in the early 1880s. Managed by Anglo-Quebecer businesspeople, French-speaking municipal officials was appeased with the arrangement so long as the anglophones’ business acumen benefitted the city.

By the 1960s, this symbiotic relationship began deteriorating – as did Montreal’s finances. In “Québec: Le défi économique,” Jacques Fortin says that Montreal’s inability to transition away from traditional industries of clothing, shoes and textiles laid the groundwork for its economic demise: from the mid-1960s until 1981, Montreal’s unemployment rate was three times higher than Toronto’s. This was aggravated by American corporations’ choice to invest in Toronto, owing to its geographical proximity to major American cities and to the lingua franca of commerce: English.

Meanwhile, spiteful feelings were building among Montreal’s citizens. Results from the federal Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism in 1966 had more of a polarising effect than a reconciliatory one: it revealed that unilingual Anglo-Quebecers earned an average salary of $6,049 – nearly 95 per cent more than unilingual ($3,107) Franco-Quebecers, and 34 per cent more than bilingual Quebecers ($4,523).

By the time the Quiet Revolution began, tensions were anchored on the Parti Québécois’ slogan “Maîtres chez nous.” In 1977, separatist premier René Lévesque concretized rumbling societal tensions into Bill 101, a French language policy that drove Anglophone business out of the province, headlined by financial institutions who relocated their headquarters to Toronto. Ironically, the list includes Bank of Montreal, founded in Quebec in 1817, and Royal Bank of Canada.

When Sun Life Assurance Co. joined the exodus in 1978, it cemented the economic swinging of the pendulum away from Montreal. Brokers at the Montreal Stock Exchange called it “Black Friday” on Montreal’s already sluggish economy, while Quebec finance minister Jacques Parizeau reprimanded Sun Life as “one of the worst corporate citizens Quebec has ever known.”

According to the Fraser Institute’s report, “Interprovincial Migration in Canada: Quebeckers Vote with Their Feet,” an average of 13,238 more Quebecers emigrated from than immigrated into the province, making it the only province to have experienced a yearly loss from 1971/72 to 2014/15. Emigrants numbers peaked in 1977/78 at 46,429 – coinciding with Bill 101’s implementation.

As the French would say, Toronto truly ‘profited’ from the influx of businesses, according to Statistics Canada data. From 1976 to 1982, individual accounts rose nine-and-a-half-fold to $4.4-billion from cashed cheques. In comparison, Montreal saw a threefold increase to under $800-million during that time.

Between 1972 and 1980, the Toronto CMA’s value of exported goods increased by 166 per cent while the number of manufacturing establishments increased by 17 per cent.

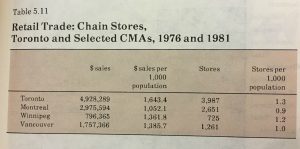

In retail sales of the period, Toronto again had the upper hand on Montreal: there were 1.3 chain stores to serve every 1,000 Torontonians, compared with 0.9 stores per 1,000 Montrealers.

Nathaniel Baum-Snow, a specialist in labour economics and economic geography, indicates that the French-language barrier is a burdensome regulation in Quebec that will continue to dissuade businesses.

“The Quebec government has made the choice that they prefer primacy of the French language over economic primacy,” says the associate professor of economic analysis and policy at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. “They will have to grow organically within these confines to become a stronger business location. That will be a slow process… They will not be able to attract much English dominated business from elsewhere in any case.”