While recent Twitter comments condemned the re-designs for the Château Laurier addition as “the same ugly glass structure” that “birds might enjoy pooping on,” they also echo criticisms from the hotel’s distant past.

In fact, designs for the beloved Château itself were once seen as a “blot on our government,” and an “indignity” to Major’s Hill Park’s public space, as esteemed merchant Mr. Poulin told the Ottawa Journal from August, 1907.

Public lands for private enterprise

Similar statements from ‘leading citizens’ were collected by the Journal – Ottawa’s 20th century Twitter – after the Grand Trunk Railway company revealed their designs for the expensive hotel and train station, and left a citizenry divided.

The hotel would be built at the front of Major’s Hill Park, a public space many Ottawans valued for its heritage and scenic view of the Parliament buildings. Here, the developers felt it would have unfettered access to tourists using the adjacent railroad.

An unhappy Mr Ross, of the C. Ross department store, told the Journal it would “utterly destroy one of the finest pieces of natural scenery that Ottawa has.”

J.R. Jackson, in a dramatic letter to the next day’s issue, wrote that “every man, woman and child [. . .] would say let the Grand Trunk and its hotel (and station, too, for that matter) get out of Ottawa bag and baggage, rather than surrender the choicest public grounds [. . .] to be a private promenade…”

Not all Ottawans opposed the site, however. A Dr. Kennedy expressed that most park-goers weren’t actually from the city, and “would be more struck by a handsome hotel [. . .] than they are by the Park itself.”

The Château’s architect, a New Yorker named Bradford Lee Gilbert, mirrored these claims in an urgent letter to Grand Trunk’s general manager, Charles Hays, that month. “Judging from the number of benches provided, [the park] is not used to very great extent by the citizens of Ottawa,” he wrote.

Gilbert’s letter, obtained from the Library and Archives, argued the Château’s gothic structure would “harmonize” with the Parliament buildings, and wouldn’t pose any threats to the park’s usage.

Public lands for government-gain

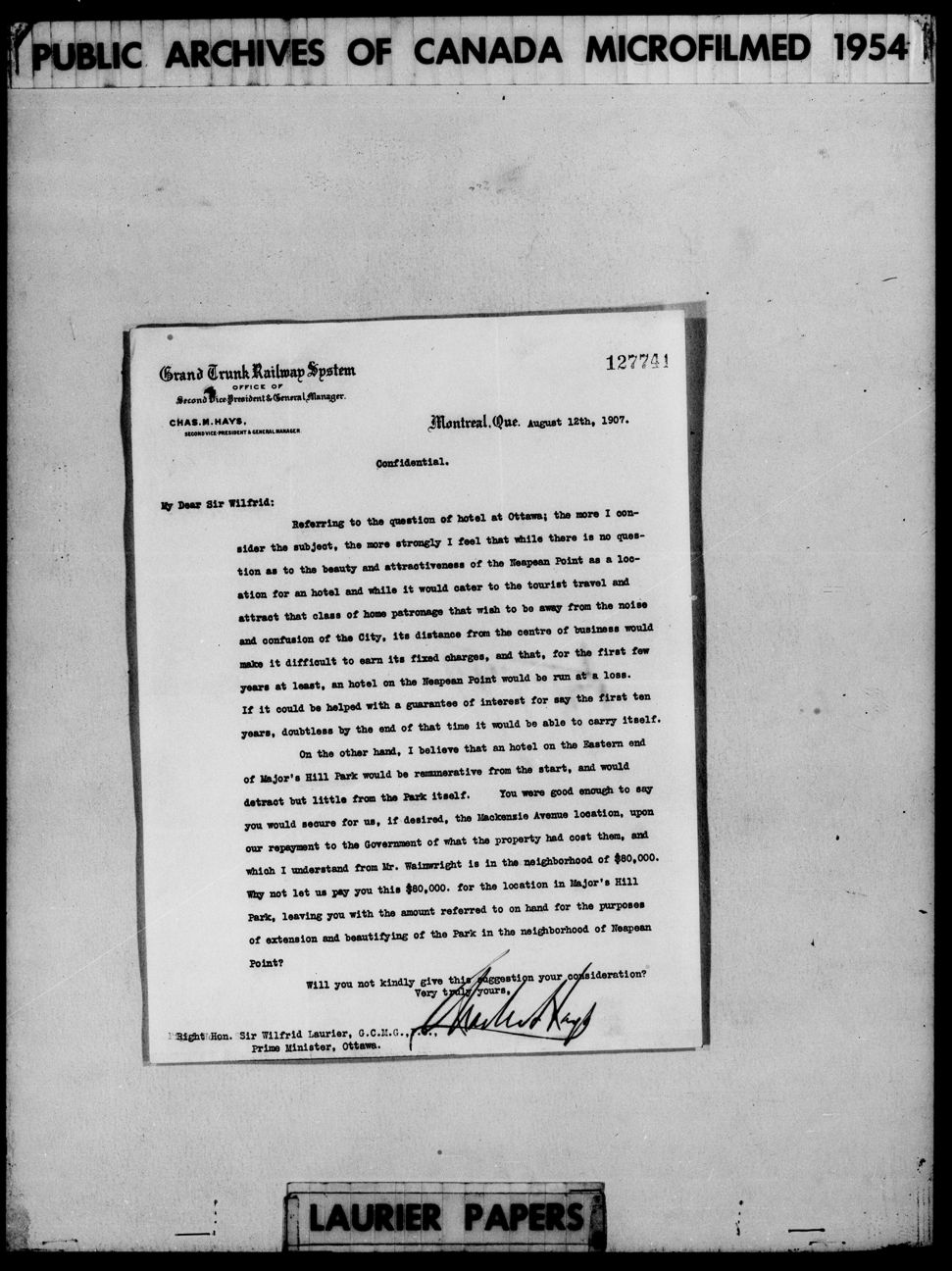

But the designs would have to win the federal government over before construction could begin. An archival letter to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier reveals the government wasn’t keen to have the hotel in a space that could be used for new government buildings instead. After Laurier suggested that Napean Point be a more suitable location, Hays argued otherwise.

“Its distance from the centre of business would make it difficult to earn its fixed charges. [. . .]For the first few years at least, an hotel on the Napean Point would be run as a loss,” he wrote to Laurier.

Laurier then contacted the Grand Trunk’s Vice-President William Wainwright three days later, claiming the hotel’s height would compete too much with Parliament. “You should ask your architect if it would not be possible to take off one or two storeys,” he suggested.

Architectural Upheaval

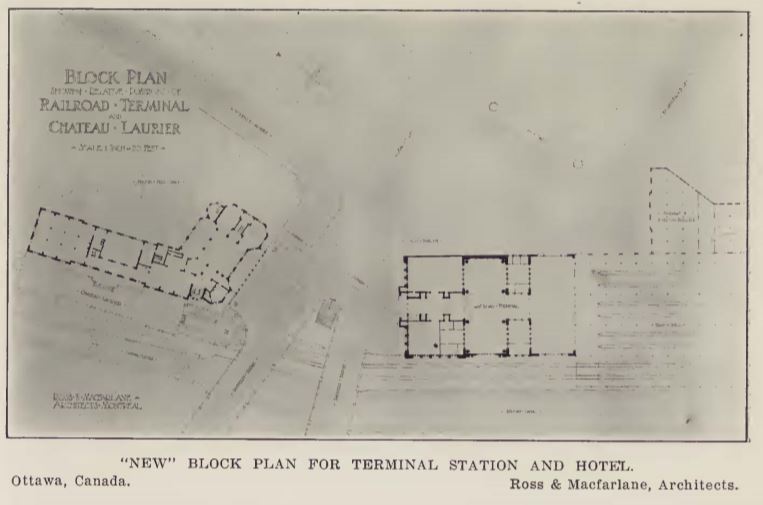

Architect Bradford Gilbert’s miserable fate heightened the controversies. His designs for the hotel and station to cost a combined $2.5 million were approved by the government, but six days before City council examined them, Gilbert received a distressing order from Hays to re-design the building to cost $1 million less.

Gilbert refused to take responsibility for the re-designs the City didn’t approve of, and was fired in February, 1908. The new firm Ross & MacFarlane soon unveiled designs that an angry editorial in the Architectural Record claimed were “identical” to Gilbert’s.

“If this be ‘architecture,’ a supply of tracing paper and a brazen front are the main requisites for [. . .] that noble art,” it haughtily states.

The hotel became controversial again when designers proposed its first expansion, in 1929.

Château historian Kevin Holland said in an email that throughout history, any changes to the hotel “reflect the respective owners’ confidence in their property and its market,” and “any controversy reflects the passionate and protective views held by Ottawans for what has long been an iconic landmark in the capital.”

And if history repeats itself, today’s new ‘disdain’ might just become tomorrow’s old icon.