A new project will help expose hidden stories about Alberta’s colonial history in March, after a three-year dispute over a mural in an Edmonton subway station.

The 25-year-old mural is in the Grandin LRT station and depicts the legacy of the French-Canadian pioneer after which the station was named. Bishop Vital Grandin was instrumental in building Alberta, but he was also infamous for running the province’s residential schools.

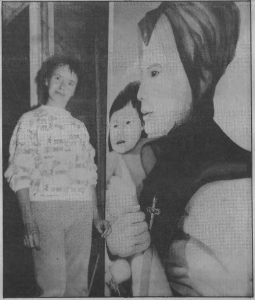

Spearheaded by the Edmonton Arts Council and the city’s Aboriginal Relations Office, the soon-to-be-unveiled art project is still very much “on the hush,” according to Sylvie Nadeau, 61, the creator of the original mural and a proud Franco-Albertan.

Nadeau revealed she was involved on the new project but could not disclose its exact form or its expected location within the LRT station. She said however it would not be replacing her old work.

“I had created it with love, I had no idea,” the artist said about her first piece, adding that she was unaware of residential schools and their treatment of First Nations back when she completed her painting in 1989.

“It doesn’t change what happened but you can create something powerful with another perspective,” she said.

According to Nadeau, the leftmost panels of the original artwork were the “controversial ones” that drove some Edmontonians to react.

Amidst the hues of blue, green, black and brown, a Caucasian woman with a crucifix around her neck is holding a Métis toddler. In the background, there is a small gathering of faceless aboriginal people and, further behind them, a four-story building with many windows that resembles a residential school.

For some passing through the high-traffic LRT station, the mural might only be part of the décor but, for others, it still triggers unbearable memories.

In February 2011, an article published in the Edmonton Journal brought survivors of the notorious schools to speak out, the artist said. The criticisms of Nadeau’s work spread like wildfire—to the point that aboriginal and francophone community leaders were compelled to sit together and find a solution.

“Nobody talked about that mural for almost 25 years. And then, it stirred up so much controversy,” said Nadeau, who was willing to have the panel with the woman and child taken down.

But the city has rules against taking down—or even altering—public art, she said. The project’s committee was left with a daunting task: to complement the perspective in the original mural with a new set of ideas, giving aboriginal people agency in expressing their version of history.

For University of Alberta professor Roger Parent, an expert in semiotics who looks at how culture is represented through signs and symbols, the project will allow long buried narratives to resurface.

“We can see how now the varnish is starting to crack,” he said. “I think it’s bringing to light the wider issue of the representation of First Nations and their history in white mainstream society.”

Parent explained that, what the artist saw as an act to protect Métis children “disowned” by First Nations, the latter interpret as a benevolent portrayal of residential schools. The meaning of an art piece, he said, is mostly constructed in the heads of those watching.

“You’re dealing with an extremely significant cultural space and, at the same time, that painting has evoked so many different stories that have never been fully told, that have never been fully understood,” he said.

By the end of March, Nadeau said, passengers can expect to see some of these different stories as they ride through Grandin station.

“It’s not just about two ethnic groups,” the artist said.

“We’re all in this together.”