Image Source: The Daily Mirror, May 20, 1916

BUILDING A WAR

By 1916, Great Britain was burning through its timber supply, and sourcing 70 per cent of its lumber from Canada had become unsustainable. Cargo space was nonexistent onboard transport vessels that were busy dodging German U-boat attacks on the trans-Atlantic journey. In February 1916, Great Britain demanded help from Canada, and two months later, 1,600 cross-cut-saw-wielding Canadian lumberjacks were sailing to Europe. By Armistice Day in 1918, nearly 24,000 men made up the Canadian Forestry Corps.

With trenches and tunnels drenched and rotting in the French rain, the demand for lumber seemed as perpetual as the war itself, says Maj. Michael Boire, historian at the Royal Military College of Canada. “You just don’t build something once on the Western Front, you rebuild it every other week.”

TIMBER TO TRENCHES

When the call came from command in March 1918 for 500 additional Canadian soldiers to join the front line, 1,300 Forestry Corps men volunteered. Meanwhile at home, Prime Minister Robert Borden struggled to muster the same enthusiasm, and had resorted to a severely unpopular conscription law to fulfill his promises to Great Britain.

“Sure, the volunteering was oversubscribed [compared to that in Canada],” says Boire of the overwhelming response amid the Forestry Corps. “But that’s a typical reaction of the boys up front,” he explains. “They had to go home someday to answer the question, ‘What did you do in the war, Daddy?’” Volunteers compelled by notions of duty and honour spurred the surge in enlistments.

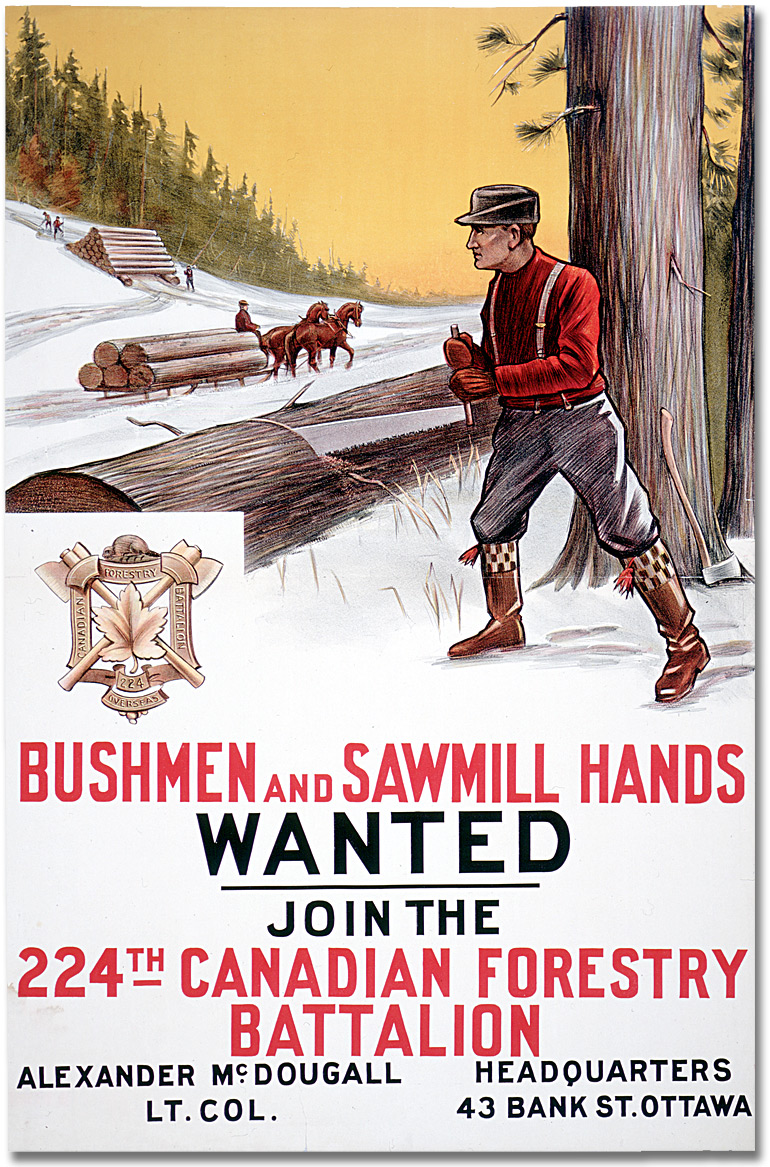

Image Source: Archive of Ontario, War Poster Collection

Working deep in forests away from the front lines, the lumberjacks were not necessarily considered brave soldiers, says Boire. By 1918, many had resolved to prove their compatriots living and dying in trenches wrong.

Still, some saw the Forestry Corps as a means of avoiding battle. In a letter to his mother, front-line soldier John Row wrote of his uncle in the Forestry Corps: “he is a wise guy alright but it would look better if he took a spell at the front. There are too many of these heroes who stay in England.”

Meanwhile in Canada, some politicians doubted their usefulness. “It is felt the Forestry Corps staff is a refuge for personal friends of those in higher command,” argued opposition MP Rodolphe Lemieux in a parliamentary committee in April 1918.

Lemieux wasn’t alone in seeing a poorly functioning Corps. Newspapers in Great Britain reported it too. “A tremendous number of administration problems have to be worked out—from the handling of a special hospital service for the Corps to the proper handling of the discipline for the men, who are not trained soldiers, and a thousand other questions,” reads the Dec. 28, 1917, issue of The Scotsman.

FOREST FICTIONS

Despite negative reviews, the Canadian Forestry Corps kept chopping, cutting, milling and sawing. In one day at a La Joux mill in France, workers produced enough timber to build 11 modern-day three-bedroom homes.

The Corps’ unbelievable productivity was praised by government and media alike. The same critical article from The Scotsman wrote that “[The Corps’] monthly output, if it could be published, would read like fiction,”echoing the words of the British Secretary of State for the Royal Air Force, who suggested that 170 Canadians could easily do the work of 600 Britons.

The First World War ended nearly 100 years ago in November 1918 and the mills in France, England and Scotland lurched to a halt. Trees regrew and forests renewed, and though saws and gears rusted in the camps, they would be raided again 20 years later by the return of war and with it, the Canadian Forestry Corps.