The agency responsible for the fleet patrolling Canada’s waters has trouble meeting the expectations set out for it by government, often sacrificing “needed” investment in its ships and relying on temporary funding to make ends meet.

According to a briefing book, received under the Access to Information Act, and prepared earlier this year for Hunter Tootoo, former Minister in charge of the department of Fisheries and Oceans, indicates the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) is now in dire straits with little hope for an immediate solution.

The Silent Service

Rob Huebert, Associate Director of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies and expert in Maritime security, described the CCG as a “silent service” — often asked to do more than anyone would think is reasonable, but always succeeding.

“We’re constantly in this bizarre situation where we completely and utterly rely on them for a whole host of issues,” says Huebert. “But the [restructuring] of the coast guard’s capabilities are not in a happy state.”

In the past 11 years over $7 billion has been committed to renewing the CCG.

But the majority of replacements for the CCG’s larger ships are not expected to arrive until 2025. Until they do, an estimate from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans says 83 per cent of the CCG’s budget is required to maintain the agency’s state of readiness.

An Aging Fleet

Even 15 years after retirement, Captain Harvey Adams still fondly remembers his time serving aboard the CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent, one of the two remaining large icebreakers in the CCG’s fleet. During his 33 year career with the coast guard, he served aboard the ship when it was launched in 1969 and eventually became its captain.

“It was the biggest ship, the most powerful ship probably in North America at the time. Even the American’s couldn’t have matched it,” says Harvey, recalling his first thoughts of the Louis.

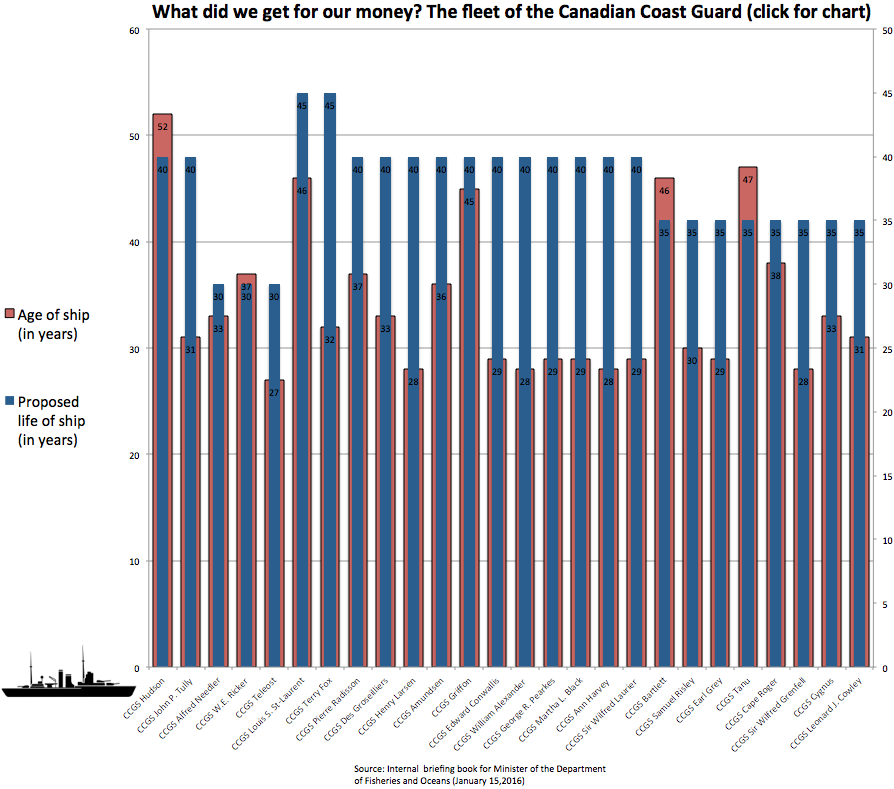

But that was 46 years ago, and like 31 per cent of the CCG’s current fleet, the Louis has aged significantly – putting the ship past its expected life cycle.

According to an analysis of documents included in the DFO briefing book, the figure will increase to 54 percent within the next five years.

Replacement

Some replacements ships are on their way. The replacement for the Louis, the CCG John G. Diefenbaker, will be the first to come off the line. While it was originally expected to arrive next year, construction is not expected to begin until 2022 at the earliest. It’s now scheduled to arrive in 2023.

Huebert says as a result of the National Shipbuilding Strategy – a long-term project to rebuild the nation’s fleet that prioritized providing ships to the Navy – the Louis will likely remain in service until the Diefenbaker arrives.

“When you think of something lasting from ’69 until now most people would go ‘Holy Moly! I wouldn’t be driving a car that is that old,’” says Huebert, “That is unless you’re into antiques.”

The Future

The new Minister for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Dominic LeBlanc, did not respond to a request for comment.

But with the mandate letter for the Minister of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans indicating a commitment to the National Shipbuilding Strategy, it appears the CCG is stuck on its current course.

For men like Adams, who spent most of their lives on the deck of a vessel it isn’t about the age of the ships they crew, or when new ones will arrive. It’s about the life he built on the water.

“The Coast Guard is one of the best jobs going to sea in Canada,” he says. “I have so many good memories it’s hard to remember just one.