How community justice programs are reducing youth incarceration and rebuilding partnerships in the N.W.T.

By Erika Stark

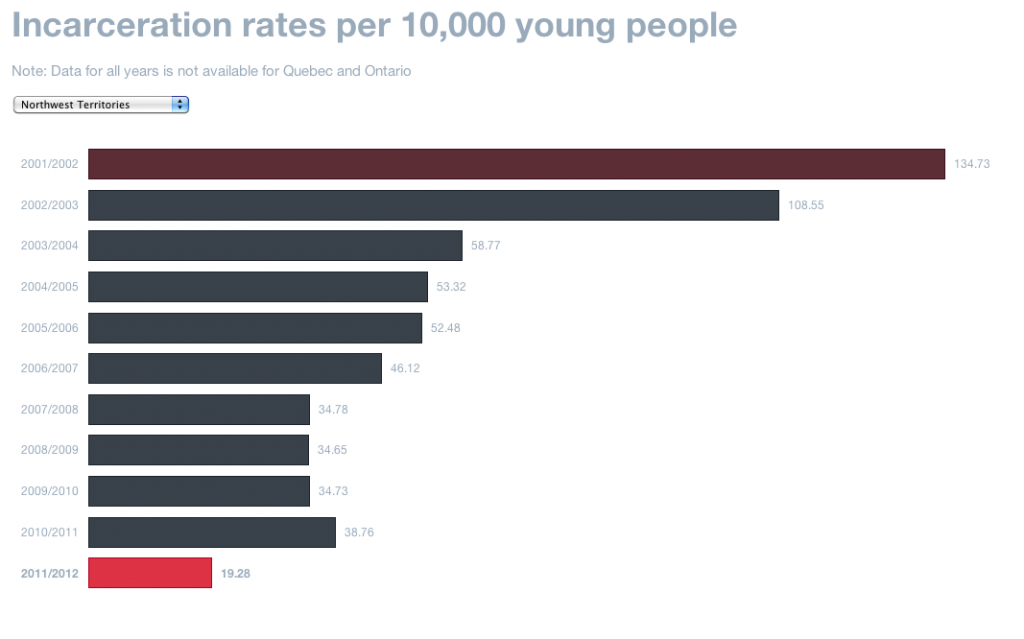

It still has one of the highest rates of youth incarceration in Canada, but fewer young people in the Northwest Territories faced criminal records last year than they did a decade earlier, statistics show.

Community focus on restorative and rehabilitative justice measures, rather than criminal charges, has changed the way young people interact with the justice system in the N.W.T.

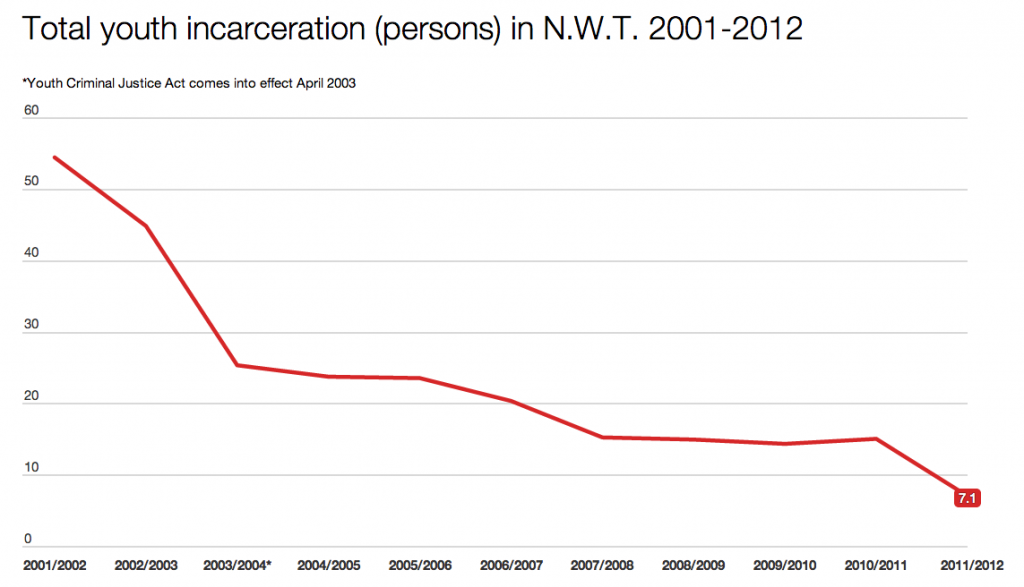

And, according to Statistics Canada, the youth incarceration rate has dropped 86 per cent between 2001 and 2012 – the largest decrease anywhere in the country.

It’s important to note that because of the small population of the territory, a year-to-year difference of a few people can significantly skew the data. For example, the data shows that between 2010/2011 and 2011/2012, the incarceration rate per 10,000 young people dropped by more than 50 per cent, and that’s because there were 15 young people incarcerated in the first year, and seven the next. Still, over the whole 10 years, the actual number of incarcerated youth has steadily gone down.

It’s partly because of the change in Canada’s youth crime legislation 10 years ago, says Dawn Anderson, the director of the community justice and policing division for the N.W.T’s justice department.

The Youth Criminal Justice Act, which requires police officers to consider extrajudicial measures such as warnings and referrals before charging people under 18, came into force in April 2003. The alternative measures cause less young people to end up in court and, possibly, in prison, she says.

It also means that the rates of youth incarceration nationwide before 2003/2004 are significantly higher because of the change in legislation. Still, the steady decrease in the N.W.T. speaks to the success of the territory’s community justice programs, says Anderson.

The extrajudicial approach is important especially in the territory’s smaller communities – some with less than 100 people, she says.

“People know each other,” says Anderson. “They’re able to draw on their strengths and the resources in their community to ensure the sentence fits and is feasible for the youth.”

When a young person is diverted from the court to a community justice committee, he or she will not have a criminal record, and his or her sanction will be tailored to what works best for the community, she explained.

“It allows for them to repair the harm to the victim and the community where the offence occurred,” Anderson says.

Thirty out of the N.W.T.’s 33 communities receive yearly funding from the community justice division to run their own programs, which also include crime prevention programs, relationship building, and what Anderson calls “on-the-land” cultural programming.

“There’s a strong focus on cultural and traditional activities,” she says, adding that strengthening relationships between youth and elders is another priority.

Requests for funding have become increasingly consistent throughout the territory, and Anderson says it’s a sign these programs are working.

“The biggest strength of the community doing this is that they’re resolving and addressing issues,” she says. “It empowers them to create a safer community and it creates a partnership. Collaboration is huge for us.”

Despite the drop, youth incarceration rates in the N.W.T. remain among the highest in the country and, at 19.3, are well still over the national average of 7.6. It’s a work in progress, says Anderson.

Her department is piloting a community safety strategy in Tulita, Hay River Reserve and Inuvik, and she says they’re constantly reevaluating their programs.

“We’re not only looking at the youth,” she says. “We’re looking at the adults, we’re looking at the victims, we’re looking at support services and making sure it’s culturally relevant.”

_____

LISTEN: Dawn Anderson describes how community justice committees in the N.W.T. benefit youth.

Audio Player