The doctrine of judicial immunity is a principle wedded to Canada’s court system. It protects federally-appointed judges from scrutiny while immunizing them from civil liability from both plaintiffs and defendants who believe their interests were harmed by judges.

The principle of judicial immunity has been upheld by Canada’s Supreme Court in at least two decisions, the most recent being Mackeigan v. Hickman, [1989]. Black’s Law Dictionary defines judicial immunity as [the] term that describes the immunity that a judge has from civil liability for actions performed as a judge.

The rationale for judicial immunity is two-fold: it is said to be in the public interest that judges can exercise their duties and adjudicate matters before them free of external coercion or pressure; and that such duties are executed without fear of reprisals or litigation by parties who feel wronged by their decisions.

The principle of immunity does not immunize judges from inappropriate conduct or comments they make within their scope of duties. The Canadian Judicial Council is a body that accepts complaints from the public who believe a judge has behaved inappropriately within their adjudicative capacity. It cannot, however accept complaints about the decision-making role ambit of a judge, nor any errors in law he or she made that was later reversed by an appeals court.

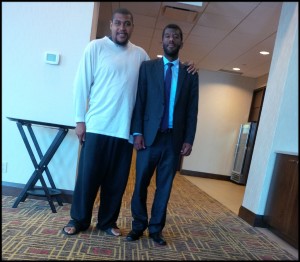

Lyle Howe is a Halifax lawyer whose odyssey through the justice system began in 2011. A night of socializing led to a sexual assault charge that wound its way through the courts until the charge was dropped by the Crown in Feb. 2016.

The defendant sat through a preliminary hearing in 2012 followed by a trial by jury in May 2014. After a month-long trial he was convicted of sexual assault. It wasn’t until Sept. 2015 that an appeals court decision by three judges set aside that conviction.

Credit: Mary MacDonald

The three-judge appeals panel found that the presiding judge at trial made errors in law in his instructions to the jury. In an interview below, the defendant talks about the aftermath of that conviction and reflects on how the outcome may have been different had the judge not erred in both his decision-making and instructions.

An excerpt from R v Howe, 2015 NSCA 84 annotated in DocumentCloud

(click inside the annotation to see the entire document and other annotations)

Source: http://www.canlii.org/en/index.html

An excerpt from R v Howe, 2015 NSCA 84 annotated in DocumentCloud

(click inside the annotation to see the entire document and other annotations)

Source: http://www.canlii.org/en/index.html

An excerpt from R v Howe, 2015 NSCA 84 annotated in DocumentCloud

(click inside the annotation to see the entire document and other annotations)

Source: http://www.canlii.org/en/index.html

Howe realizes that answers will likely never be forthcoming to reconcile the trial judge’s decision-making. He is absolved from explaining errors – as are all members of the judiciary – by the doctrine of judicial immunity.

Interview with defendant Howe

Audio Player

In cases where a defendant is adversely affected by a judge’s errors in decision-making, the legal system offers no remedy other than the option of appeal. It does not recognize the proposition that the public interest may not be served if defendants experience adverse impact as a result of judicial errors.

As explained by legal scholar Adam Dodek, there is no mechanism in place to track the errors a particular judge makes during his or her tenure in the courts. It is possible that a judge could make errors in law in a series of cases over time, but face no consequences because the principle of judicial immunity is virtually invincible.

Professor Dodek, a legal expert at the University of Ottawa, explains that the doctrine of judicial immunity has been affirmed by the Supreme Court, and has not been successfully challenged in the lower courts.

In particular, Dodek rejects the theory that a defendant could be stigmatized by the consequences of a judicial error of law resulting in conviction.

Interview with legal scholar Adam Dodek of the University of Ottawa

Audio Player

Until the doctrine of judicial immunity is overturned, defendants have no civil recourse to judicial error other than waiting out what can be a lengthy appeals process, while being told that any adverse consequences take a back seat to the public interest.