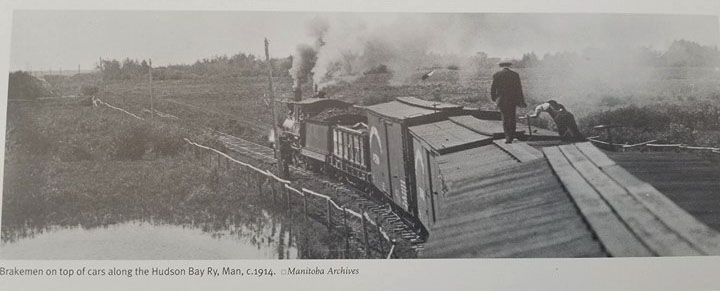

Raging blizzards, expansive bog land and unstable clay-covered bedrock greeted the men who had taken up the daunting task of completing the last stretch of the Hudson Bay Railway linking Manitoba’s capital, Winnipeg, to its only port, Churchill, in the late 1920s. Last spring however, a powerful blizzard that caused widespread flooding in the province’s north damaged that stretch of rail so significantly that the track’s owners have refused to pay to repair it, citing the large price tag.

The rail line was washed away in 19 spots along the 290-kilometre stretch, nearly the same distance as between Calgary and Edmonton. According to Omnitrax, the U.S.-based rail operations company that purchased the Hudson Bay Railway during the privatization of Canada’s railways in 1997, the link between Winnipeg and Churchill is no longer worth fixing.

Since Churchill has no road access to the south, the community’s 900 residents have been cut off from their main source of supplies. The town can now only be accessed by air, a costly alternative to rail.

It’s not the first time the railway has had trouble justifying its costly existence. In fact, from its outset in the late 19th century, the 1,700-kilometre long rail link faced pushback from both government officials and private corporations who doubted its ability to improve Canada’s economy.

According to a paper written in 1958 for the Manitoba Historical Society by Leonard F. Earl, a former Manitoba economic and political journalist who died in 1969, early Manitoba Liberal politician Hugh McKay Sutherland proposed a railway to the Hudson Bay as early as the 1880s.

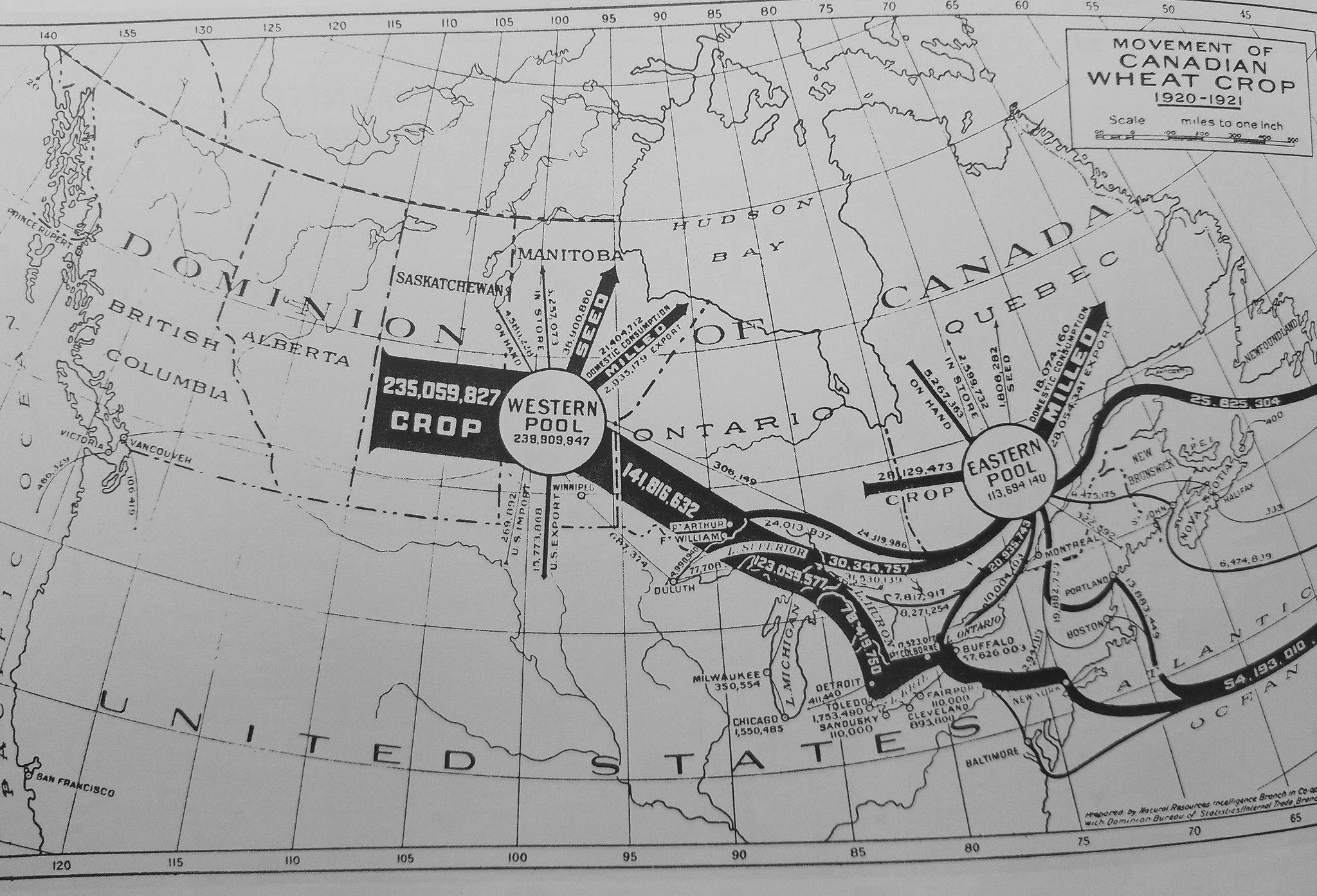

Sutherland saw the economic potential of shipping prairie grain from a port on the Hudson Bay directly to European and global markets, an alternative to the lengthy rail transportation to Canada’s eastern port cities. Sutherland however, may have overlooked the geographic navigation problems of building a railway so far north, a feat that had never been attempted before.

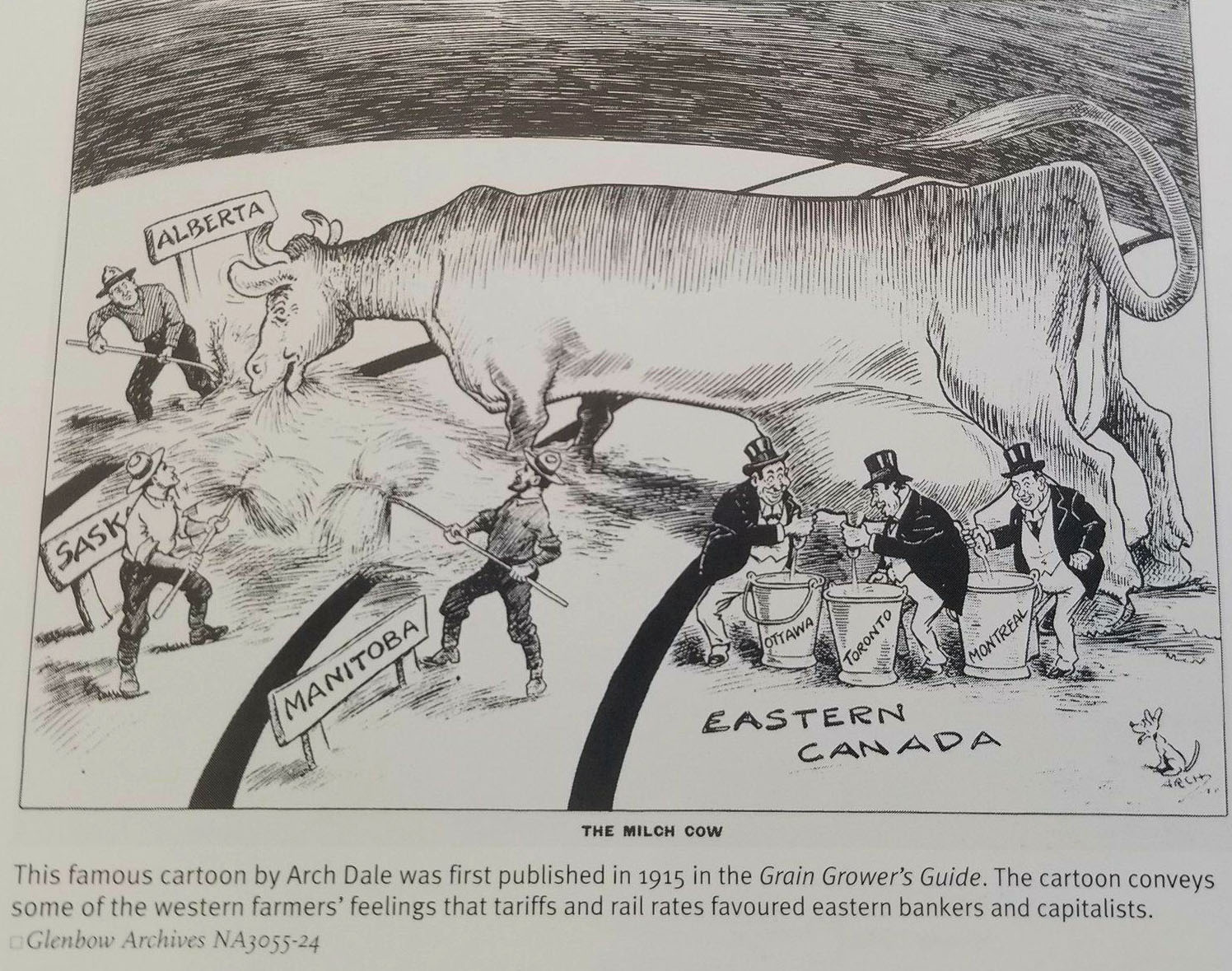

The former MP for Selkirk also faced intense backlash from Conservative politicians from eastern Canada who didn’t want to see their port cities challenged by the west.

On top of both geographic and political challenges, the return of Métis revolutionary Louis Riel to Manitoba and the outbreak of the Red River Rebellion in 1885 significantly delayed the project. By the end of the 19th century, the Hudson Bay Railway was jokingly referred to as “a crackpot dream” by politicians and railway tycoons alike, according to Earl.

Sutherland pushed forward with the project nonetheless, and despite constant funding setbacks, construction on the project went ahead in stages: first northwest to Dauphin and the Saskatchewan border due to the thousands of lakes preventing a straight push northward, then northeast towards The Pas and back into Manitoba.

However, construction was again delayed in 1914 with the outbreak of World War One and in 1926, when work on the last leg of the railway between Gillam and Churchill finally began, Sutherland passed away in England. He would never see his 40-year dream of a link between Winnipeg and the shipping routes of Canada’s north complete.

Even if he did, however, he may have been disappointed by the final result. By the time the first trains could reach the port of Churchill in the autumn of 1929, the railroad, sitting on frozen bogs and shaky outcrop, was too unstable to carry trains with heavy loads of grain.

The port, designed to ship millions of tonnes of grain to the world, only handled a fraction of that for the next few decades.

Then, after the National Wheat Board was shuttered and the port of Churchill was closed in 2016, the railway was only used to transport tourists and supplies to the remote northern town.

Last year’s flooding and the severing of an 89-year-old link to Winnipeg and the rest of Canada served as Churchill’s final kick to the shins.

A shaky dream from the start, the Hudson Bay Railway has turned into northern Manitoba’s nightmare. Now, it may be in its final days.