Although 380 religious properties across Canada were targeted in hate-related mischief between 2011 and 2015, only eight per cent of those incidents led to a charge, according to data from Statistics Canada.

Although 380 religious properties across Canada were targeted in hate-related mischief between 2011 and 2015, only eight per cent of those incidents led to a charge, according to data from Statistics Canada.

“This is a huge concern,” said Amira Elghawaby, the communications director for the National Council of Canadian Muslims, “It just begs more questions. How much resources are being put on these issues?”

Within the five-year period, 2011 had the highest number of charges. Only 13 charges came out of the 72 incidents that happened in the year. In 2015, only five people were charged despite 79 incidents.

“We know that our police services are often working with very limited budgets but it’s very important that police services take these concerns very seriously and they send a strong message to the wider community that such attacks are not going to be tolerated,” Elghawaby added.

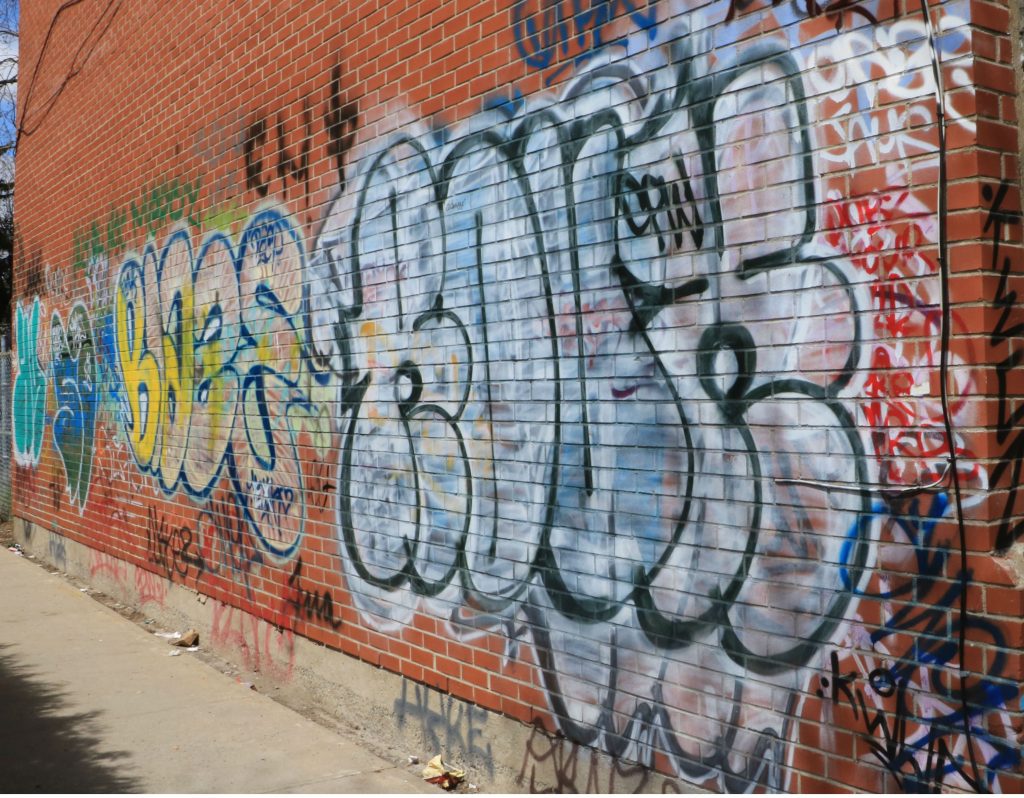

But in most cases, the culprits of these forms of mischief are not easy to identify.

“The vast proportion of mischief incidents are graffiti,” said Mary Allen, a senior analyst with the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics at Statistics Canada. “And when it’s graffiti, you have no idea who did it.”

Incidents of hate-related mischief to religious property sometimes extend beyond graffiti. In September 2016, a mosque in Hamilton was the target of an arson attack. The National Council of Canadian Muslims has a hate crimes map that tracks hate-related mischief reported to the police or by news organizations.

Reluctance to report hate crimes

Incidents of hate-related mischief to religious property may be higher than the numbers show.

“We know that there is often a reluctance for institutions to report to police,” Elghawaby said about institutions within the Muslim community.

Her organization launched a national hate awareness campaign in 2014 to educate people about hate crimes and encourage them to report. In the same year, the number of police reported mischief to religious property was 96, the highest between 2011 and 2015.

“There is a fear of being seen as a problem in the neighbourhood, being further marginalized in the community, and so sometimes there are mosques that will just quickly, if it is graffiti, they will just remove it and not tell anyone at all,” Elghawaby said.

Allen said sometimes, communities of new immigrants who may not speak English or who feel uncomfortable talking to the police, are reluctant to report when their religious properties are targeted.

“If a community has a strong relationship with the police and strong ways to communicate with the police, you can expect higher reporting,” Allen said. “Police-reported hate crime numbers are very complex because of that.”

Statistics Canada’s most recent analysis of police-reported hate crimes states that the most common categories identified in mischief to religious property were Catholic.

(To see the entire Juristat report by Statistics Canada, please click on the annotated image)

No clear cause of change in numbers

The number of hate-related mischief to religious property went from 55 in 2013 to 96 in 2014, a 74 per cent hike. Last year, that number went down to 79. But there are no clear indications as to why that is.

“It’s really hard to disentangle,” said Allen. “It’s really hard to know whether the increase in the numbers is related to reporting or incidents. It’s probably both…with so much of what we produce, you can’t be sure that it’s measuring what is actually happening out there, but it’s measuring the reporting of it.”