It’s been half a year and none of the eight Chinese graduates from the class of 2014 Master of Economics program at Carleton University has found a job related to their education, according to one of them, Xiaohu Li.

However, all of them were nominated by Ontario Province as candidates for citizenship, thanks to the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP).

Half of the eight Chinese graduates thought they would be counting the accounts of the nation, not their cashier’s till at the end of the night.

Xiaohu Li, along with his classmates Rui Xiao, Shuhan Yang and Kun Zhang are currently working as cashiers after they graduated.

Li says a few of his Canadian classmates got job offers from government agencies and banks, such as Statistics Canada or the Bank of Canada, but he failed to find any job that is related to his field. Instead, he had to change his strategy and looked for any job that would let him stay in Canada. He now works part-time at a Tim Horton’s in Ottawa.

“I just take this job as a way to practice my English,” Li says.

Rui Xiao, Li’s classmate, began working for the Starbucks in Carleton’s library since July. She says she is the only one who holds a Master’s degree, and all her co-workers are undergraduate students.

“Many of them study in food science,” Xiao says. “At least they are working on something somehow related to what they learn, but me? This job has nothing to do with what I have learned.”

Li says there is a big difference in opportunities for local students and international students. He says, “Of course my goal is to work as a financial policy maker in the government, but the very first thing the government agencies asked me at a job fair is my citizenship, and when they learned that I am not Canadian they said ‘no’ to me very quickly.”

The latest Ontario University Graduate Survey shows the difference.

The survey shows that six months after their graduation, 18 per cent of master’s degree graduates think their work is not related to the skills they acquired through their program of study.

“Although the survey doesn’t exactly show the entire picture, it still tells you something about the reality,” says Tesia Lara Bojorquez, a data analyzer from Carleton University’s Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

Bojorquez says, “If you look at the number for the average in Ontario, it also decreased by four per cent after two years of graduation as well.” That means, more people found a job related to what they’ve learned as time goes.

Li also says it may be a matter of time. He says that he will eventually find a job in some bank or a company’s financial department, just like two graduates did a year after their graduation in 2012.

In 2012, Chinese students accounted for 12 per cent of the economic graduate class. That number climbed to nearly 20 per cent in 2013, and remained at 15 per cent this year, revealed by the data obtained through a request to Carleton University’s Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

The same trend is more exaggerated in the business program. This year more than half of the new students are from China, nearly ten per cent more than last year.

In 2008, the percentage of Chinese students in the two programs was less than ten per cent (7% in business, and only 2% in economics.)

Select the year to show the percentage of Chinese students for each program in Carleton University.

Gregory Aulenback, the international recruitment officer in the Carleton’s Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs, says the number of international applicants has been increasing steadily since 2009. That is when Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) in Ontario eased its policy for international master graduates in February of that year.

Under the policy, also known as the International Student Category’s Masters Graduate Stream, Ontario’s masters graduate students can apply for their permanent residency even without a job offer.

“That means, we already semi become a Canadian once we got our offer from Carleton,” Li says that’s how he reads the policy.

According to CIC, it takes no more than two months for a master’s graduate to get his or her provincial nomination. Then it will take around one year for the person to get a permanent resident status from the federal government.

So far, 100 per cent of Li’s Chinese classmates have already got their nomination from the province, and all of them are waiting for the federal government’s final decision.

Xiaohu Li, Rui Xiao, and Shuhan Yang all think it’s promising.

“Although it’s easier for Chinese student to get a permanent residency in Canada, it doesn’t mean they can work in the field they learned or simply they want.” Yu Zhang, the manager of a Chinese Education Agency, Yu Agency, says, “there is an imbalance between the supply and demand in the Canadian job market.”

Zhang says her clients’ top three choices of graduate programs in Canada are economics, mathematics and business. However, the Labour Force Survey from Statistic Canada shows the picture of its labour force is different from students’ choices.

Select the year to show the percentage of labour force in different fields in Canada.

In the past decade, finance ranks eighth, with only about six per cent of the labour force. Business ranks even lower, with an average of about four per cent of the labour force working in this field.

After being shown the data, Zhang says, “I think even local Canadians have the same problem in terms of finding a study-related job. Having so many Chinese competitors is like adding frost to the snow – making the situation even worse.”

“What makes the competition fiercer is the fact that most Chinese people tend to move into the same places,” Zhang says.

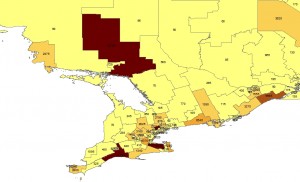

Data extracted from the Canada Census Analyzer shows that the top two destinations for Chinese immigrants are B.C and Ontario. In Ontario, Toronto and Ottawa are the most popular cities.

Zhang says, “The big Chinese community in some of the Canadian provinces will only attract an even bigger Chinese community. Therefore if Chinese students don’t want to change the provinces they want to stay, then at least they should seriously think about the programs they choose to study.”