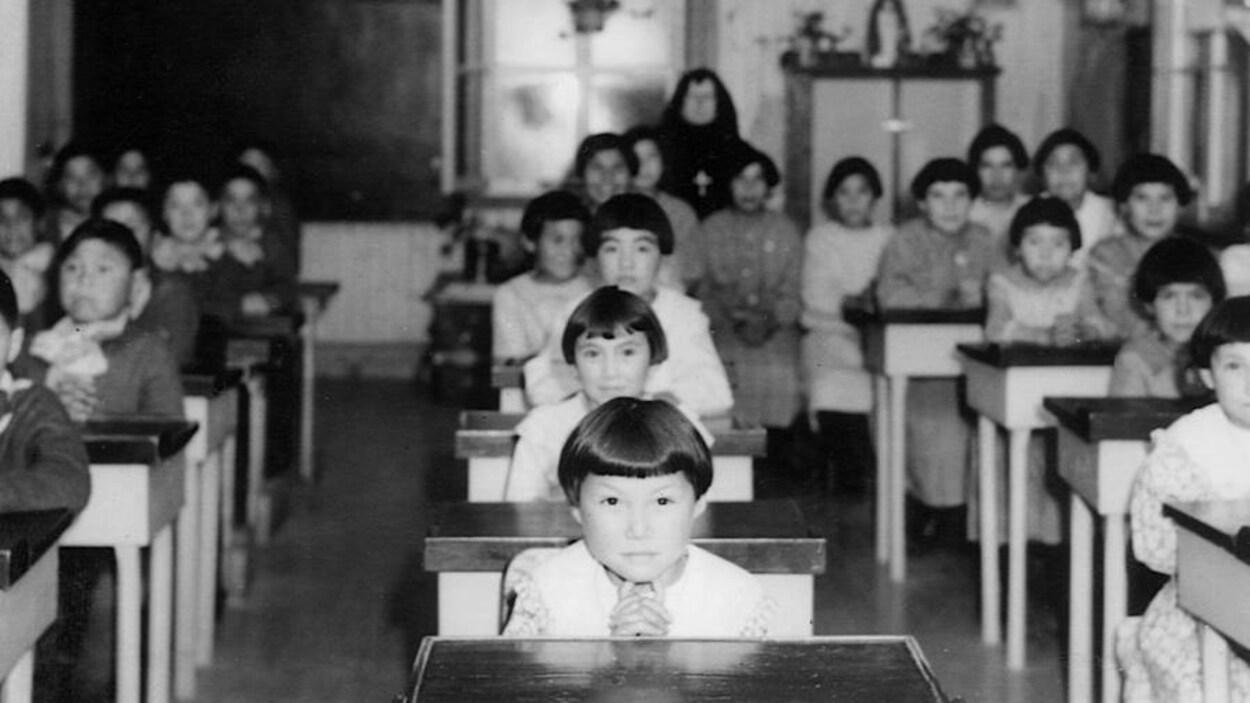

“Hearing the stories of suffering from the elderly of my band, I started to wonder why someone would want to be an Aboriginal,” said Mariette Buckshot from Kitigan Zibi, Quebec. She grew up conflicted about her identity and believes that the “Indian day schools” have a lot to do with it.

“Everybody hates our language, hates the way we look,” she recalls. “I didn’t want to be a part of that world. I wanted to be accepted socially.”

A class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of Indigenous students from Quebec who attended government-funded day schools alleges that they were “stripped” from their aboriginal identity and denied the “ability to pass on their heritage”. The legal team appraises that there are between 120,000 and 140,000 living day school survivors in Canada.

The reserve of Kitigan Zibi, Quebec, is located one hour 30 minutes north of the Canadian capital, Ottawa.

“The physical and sexual abuse, pain and distress, and the damages to language, learning, culture, and heritage,” said the filing, “were also suffered by students who were forced to attend Indian Day Schools, their descendants, and their communities.”

Allegations against the federal government contained in the lawsuit’s statement of claim have yet to be proven in court. Emailed requests to the federal government went unanswered. It has to file a statement of defense.

The lawsuit goes hand in hand with a Canada-wide class action certified last month also linked to government-funded day schools. The lawyers filed a Quebec affiliation since the legislation differs from the rest of the country.

Hopes of a harmless settlement

Mariette Buckshot, one of the two main plaintiffs of the case, hoped Canada would settle without having to go to the Supreme Court. Her father attended the Maniwaki day school from first to third grade and dropped out in fourth grade.

The Attorney General contested the class action on June 4, meaning the case is most likely going to be ruled in Court. “We wish the result will be a settlement that we, First Nations, consider favourable to all the victims,” said the plaintiff.

Patricia Doyle-Bedwell, a professor of aboriginal studies at Dalhousie University, agrees.

“I hope that the Crown doesn’t prolong the case, that they read the history, recognize the survivors’ experiences, and provide a settlement that is sufficient,” after the long process that was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. She believes that the Crown contested the case for financial reasons, since it already spent a lot with the residential schools’ settlement.

The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement is the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. More than $five billion were paid to residential school survivors.

That previous win may be beneficial to the First Nations fighting for justice against the day school system, according to Doyle-Bedwell. “It will be harder for the Crown to prove that they didn’t suffer as much as the Indigenous people who attended residential schools, because the experiences are very similar.”

The Crown is most likely going to distinguish the two cases by saying that the kids got to go home every night, said the law professor, or argue that the bands were pushing to get schools within the community. “But, these are not valid arguments because the harm still happened. There was a breach of the government’s fiduciary responsibility, just like in the residential schools’ case.”

Passing on a hurtful heritage

“My dad is 86 years old and was victimized on the reserve day school,” confides Mariette Buckshot. “It impacted him in a way where he quit school when he was only in grade four. He didn’t want anymore to do with education.” Later on, when he had kids, he insisted that they go to school while keeping their knowledge of the language and their culture.

The bands can’t overcome such a past in one generation, though. The teachers, which were most of the times nuns and fathers, kept telling the students that they were “heathens, pagans, savages and that their parents would go to hell,” says Doyle-Bedwell. “These things really cut at the heart of our identity and who we are as Indigenous people.”

When asked about what would help the healing of the First Nations, Mariette Buckshot is resolute. “Through apologies, payments and programs that go towards the healing of our people.”

“Give us back our respect. We still exist and are resilient enough to still be vocal.”