She only had two options: keep her son in the car or bring him into the store to risk contracting COVID-19. That’s the reality for many single parents during the pandemic.

“If I want to go grocery shopping or do anything he has to come with me,” the Barrhaven resident explains.

The Ottawa neighbourhoods with the highest total COVID-19 rates are also the ones with a higher percentage of single parent families, according to an analysis of Ottawa Public Health data which tracks COVID cases excluding cases in long-term care and retirement homes reported from March to October 2020.

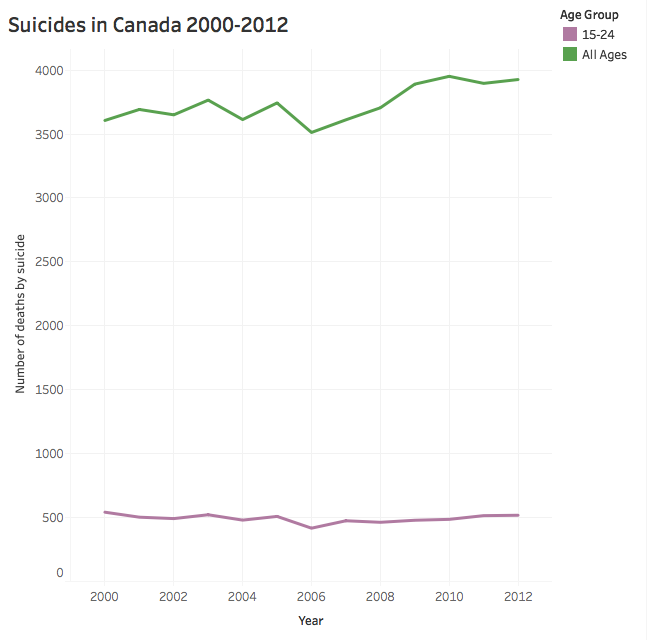

Total COVID rate per percentage of single parent families

This is the trend among most Ottawa neighbourhoods, with a few exceptions.

Single mothers are bearing the brunt, as they make up 78 per cent of single parent families, according to the 2016 Canadian Census.

This bar graph shows the top five neighbourhoods with the highest total COVID-19 rates per 100,000 people from March to October 2020. The percentage of single parent families living in these neighbourhoods are at least 20 per cent or higher. [Visualization by Yasmine Ghania]

Ivy Bourgeault, a professor in the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa who specializes in gender and health, explains there are many factors that can increase the risk of exposure for single mothers.

“Mothers tend to do the hands-on body work with children, dressing, feeding, bathing, which puts them at increased risk,” Bourgeault says. “If you are in a partnership you are disproportionately doing that work but there is somebody to share that with. As a single mom, you don’t.”

The sectors in which single moms tend to work also have an impact. “Single moms are segregated into certain labour market areas that we now call the frontlines such as the retail and hospitality sectors,” Bourgeault explains.

The low incomes generated by these types of jobs cause single mothers to live in higher density housing which furthers their risk to the virus, Bourgeault adds.

Samantha Pha, 40, is dreading going back to her sales associate job at a big-box store as she’s a mom to a nine-month-old daughter. The Britannia resident has been on maternity leave since March and has been able to get half her income during that time but must return to work in February.

She’s afraid of potentially bringing the virus back home to her baby who has had some medical issues including frequent fevers.

“My concern is her safety above and beyond everything because she’s my one and only,” Pha says as she begins to cry.

Samantha Pha, a single mother to a nine-month-old baby, describes her fears of going back to work in February in a big-box store. She didn’t feel comfortable sharing the name of the store. [Photo © Samantha Pha]

Pha chose to become a parent without a partner and went through a sperm bank.

“I said to myself ‘by the age of 40, if I don’t have a reliable partner who is willing to have children with me, then I will do this on my own,’” Pha says.

She gave birth to baby Eleanor just four days before Ottawa went into lockdown.

Poliquin is also concerned about her son’s safety as she struggles to find a childcare centre to accommodate her work schedule. As a hairdresser at exhālō Spa, Poliquin has to work many long evenings and weekends.

With the rest of her family in Sherbrooke, Quebec, her son often has to go to his friend’s house after school, who they have included in their bubble, to wait for his mom to finish work.

“The last thing I want is to have a stranger in my house to come babysit,” Poliquin says. “Most of my friends are working in the public so I don’t want them to take care of my child when they are exposed to a lot of people as well.”