Carlington’s public housing complex is a place where people land if they need to get back on their feet. The problem is getting out of the highly concentrated social housing complex built in the 80s. You have two options: one you either manage to improve your socioeconomic status and move out of the area or you apply to transfer to another subsidized housing unit.

The wait times for social housing in Ottawa can be up to five years, and according to Ray Sullivan, executive director for Centretown Citizens Ottawa Corporation – a community-based non-profit housing corporation for low and moderate income people – 20 per cent of those requests are from people seeking transfers to other types of social housing.

Joanne*, 60, lived in one of the high-rise apartment buildings on Caldwell Avenue for 18 years with her daughter Sarah. She recently received a transfer to move to another subsidized housing unit after a domestic incident. Domestic violence and overcrowding are two circumstances that are given priority if you are on a waiting list.

“The reason why it’s hard is because once you’re in a community like this – low income – to put your name on a transfer list, it’s very hard to get out of here unless you have a valid reason. You can’t just up and go because you don’t like the area.”

Joanne says when they first moved to Caldwell it was fine until the social problems and issues with the living conditions began to emerge.

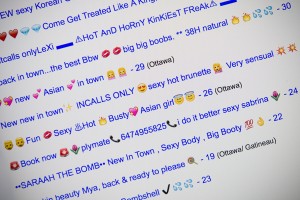

“Everything was okay until the alarms would start, but there was a drug-house right across from us, other problems in the building like drug dealers and prostitutes.”

“The fire alarms would go off any old time, sometimes that would be if it was for a fire, but very rarely, more because people were just pulling the alarms. As a lot of us knew sometimes it was being pulled by some drug person who was wanting to get in (the building).”

According to the Ottawa Neighbourhood Survey, the Carlington neighbourhood has five times more social and affordable housing units in the City of Ottawa at 1,200, compared to the average and is one of the least socio-economically advantaged neighbourhoods in the city.

Another long-term resident Andrea Terry is the first to admit the public housing complex has issues, but she wants people to see how vibrant the tight-knit community is.

“The biggest problem with areas like this is people just assume, they don’t know people’s situation. For the longest time I couldn’t tell you where I lived because of the stereotyping and because of the bad reputation this area has,” Terry said.

“Now I come out and say ‘yes I do live on Caldwell’, ‘yes I live on ODSP’…I am not embarrassed by any means, because you know what home is where the heart is.”

Map data sourced from 2011 National Household Survey

The crime and social ills are only one aspect of the neighbourhood which has a strong community presence united by a desire to support each other. Resources like the chaplaincy, foodbank, clothing depot, community centre and family centre are located inside the community. In the middle of the day residents descend on the family centre for a free big breakfast or take part in the language lessons that are offered next door.

Cst. Kevin Williams with the Ottawa Police Service is a community police officer who offers support to the Carlington community and occasionally helps out at the foodbank.

“I’ve sat on committees with Andrea and it’s awesome the dedication that they have and it’s great. It just makes you want to be involved and be a part of this. It’s refreshing to see that,” Williams said.

“It’s too bad because Carlington is a great place and sure there might be one or two incidents that might happen and it doesn’t reflect what this community is, it’s a great community.”

*Joanne declined to use her last name out of privacy.