There are some moments in Canadian history that are unforgettable. And then there are others Canada seems eager to forget.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge, a triumph for Canadian troops in the Second World War. One of these troops was Zennosuke Inouye, who fought in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force for the escarpment in Vimy.

Originally, Inouye was not allowed to serve in the war. Linda Kawamoto Reid, an archivist for the Nikkei Place, says this stemmed from a distrust of Japanese Canadians.

“There was this ‘how could you trust a Jap working beside you?’ mentality,” she says in a phone interview.

Despite the conscription laws of the time, Inouye was rejected by the Dominion military authorities in British Columbia because he was of Japanese descent, according to an article in The Canadian Historical Review. Determined to serve his country, he and 222 other Japanese Canadians enlisted in Alberta.

In April 1917, Inouye had just fended off trench fever and was previously wounded in the Battle of the Somme. At Vimy, his upper arm was torn apart by shrapnel, and he spent almost two months in the war hospital in Bristol. When he arrived back home in Canada, he purchased land near Surrey, B.C. to start a fruit farm for him and his family.

History professor Peter Neary of the University of Western Ontario writes, “He was loyal to his family and to his adopted country. In the case of the second loyalty, he now had a scar on his arm to prove it. This was a badge of honour that gave him a new identity as a Canadian.”

On the third anniversary of Vimy Ridge, Japanese-Canadian veterans were honoured with the erection of a memorial in Stanley Park, Vancouver. Atop the monument, an eternal flame was lit.

Inouye may have thought he’d never have to fight for land again. But 25 years later, he did.

This year also marks the 75th anniversary of the internment of Japanese Canadians. In 1942, the Privy Council relocated over 12,000 Japanese Canadians in B.C. to internment camps. Among the thousands were 58 Japanese-Canadian veterans of the First World War. Inouye was given a number, 03243, and separated from his sons.

Inouye’s farm land, which he had rented to a neighbour before he was abruptly relocated in an attempt to protect it, was claimed by the secretary of state and resold to the incoming veterans of the Second World War. The custodian of the secretary of state deemed this land “enemy property.”

In a letter of protest to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, Inouye wrote, “Your petitioner believes that his loyalty to Canada has been well tested in the great war, and that it does not seem fair for the government to take away from one ex-service man a property so dear to him in order that it may be given to [a] soldier returning from the present war.”

Inouye wasn’t the only veteran who felt forgotten. “One veteran caught up in the government sweep threw his medals into the Skeena River in disgust,” writes Neary.

While the government sent these veterans to detention camps, the flame on the Japanese Canadian War Memorial was extinguished.

Eighty letters between Inouye and various recipients have been found and archived by the Nikkei Place as he fought to get his farm land back. Five years after the war, Inouye was the only Japanese-Canadian veteran to have his land returned to him. His home had burned down the year before he returned, and was only ensured for $300 by the custodian of the secretary of state. At age 64, Inouye had to rebuild.

Despite the racism that Inouye and bother Japanese Canadians faced, they continued to serve in Canada’s army. Mixed race Japanese Canadians, and those married to caucasians, were excluded from internment, and about 160 enlisted to serve in the Second World War as interpreters. Japanese Canadians deported to Japan after the war were later recruited to serve with the Canadian troops in the Korean War.

Reid says she recently interviewed a Japanese Canadian veteran of the Korean War and asked him why he agreed to serve a country where his people had faced so much discrimination. The man told her he feels Canadian and loves this country.

“I think they felt they could make a difference,” she says. “It was a statement.”

So why don’t most Canadians know about this?

“I don’t think it’s well-documented, talked about or illuminated,” Reid says. “I would encourage Canadians not to buy into that.”

*****************

Notes about documentation for my professor:

There were other documents that I wanted to use from the Nikkei Place. On their website, it said “copyright: open access” so I assumed I could use that. When I did my interview with the archivist, she informed me that I could not use them without submitting a form, so I submitted one. I have not heard back yet (I’ve followed up, but haven’t gotten a response) , so I went in a different direction. Instead, I hyperlinked the Nikkei Place collection so readers could view it if they were so inclined.

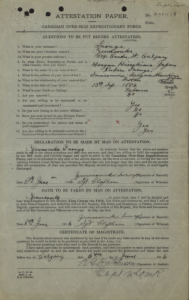

1) Attestation Paper: the very first document a soldier signs in order to enlist in the expeditionary forces. I liked this because it clearly showed his name and the force he served on. This would have been a great personal victory for Inouye, who travelled all the way into Alberta in order to enlist. I found it on Archives Canada.

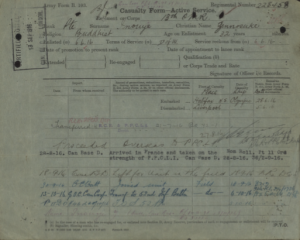

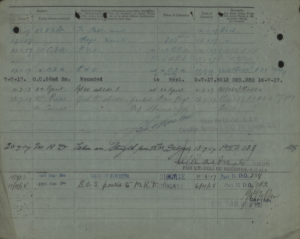

2) Casualty form: a form that records the relocations, injuries, and deaths of any individual soldier. Though this one is harder to read, you can see clearly on the first page when he was sent to France, and on the second page when he was wounded. I found it on Archives Canada, where I also found information on how to read it.