As we inch closer to the 2014 municipal election, local politicians are on double duty – fulfilling their roles as city councillors and mayor, while positioning themselves to start campaigning as early as January 2, provided they immediately register as candidates. As with any election, getting voters to the polls is essential.

But voter turnout in Ottawa’s last three municipal elections has been mediocre at best. In 2003, only 33 per cent of Ottawans voted in the municipal election. 2006 was a good year, with 54 per cent of eligible voters casting a ballot. Numbers slid by nearly 20 per cent, though, in the 2010 election, when just 44 per cent of eligible voters showed up to vote. This information was gleaned from analysis done using municipal elections data available on the City of Ottawa website.

Overall, Ottawa compares fairly well to other major cities in Canada. In the recent Montreal mayoral election, around whose candidates there was particularly heated debate, only 43 per cent of voters had their say. Fifty-three per cent of Torontonians cast ballots in the 2010 municipal election, electing Rob Ford in what was also a controversial election. Even the 2010 Ottawa elections were intense, when there was a mayoral showdown between ex-Ottawa-mayors Jim Watson and Larry O’Brien. Yet, the voter turnout still slipped.

This goes to show controversy doesn’t necessarily mean more voters hitting the polls, making it difficult to predict voter turnout in municipal elections. Ottawa’s extreme fluctuation in voter turnout between 2003 and 2010 leaves some experts scratching their heads to come up with innovative ways to engage voters.

Professor Alan Walks, who teaches political geography and urban voting behaviours at the University of Toronto, said instituting mandatory voting, like in Australia, is the way to go.

But political science professor Neil Wiseman, also from the University of Toronto, disagrees. He says he would rather have fewer people voting than force people who have not educated themselves about the issues to vote.

Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson said that “during, but more importantly between, elections, it’s very important to speak to residents in their communities about what they want to see for our city.” He also pointed to using social media as a way to “take part in discussions where they are already taking place.”

While that is a unique suggestion and one that is not often heard from academics on the subject, the debate over how and if we should try to engage new voters isn’t a new one. But all of this still begs the questions: Why do, at best, only 50-odd per cent of eligible voters actually vote? What motivates someone – or dissuades them – to vote?

Municipal elections expert from Carleton University, Katherine Graham, says she believes candidates’ lack of party affiliations plays a major role in why people don’t feel the same need to vote in municipal elections as they do in provincial or federal elections.

Voter turnout in the 2011 federal election was still weak, with 61 per cent of eligible voters turning up to vote. This is still marginally better than Ottawa’s municipal turnout. Provincially, the 2011 Ontario election brought the worst voter turnout in the province’s history, with only 49 per cent turnout. Still, the province’s lowest is much higher -16 percentage points higher – than that of Ottawa.

In federal and provincial politics, there can also be a tendency to vote for a party in order to keep an opposing party out of office. Without parties to, effectively, vote against in municipal elections, voters may see themselves voting in favour of someone. Voters may feel less passionate about a candidate than they do about not seeing another candidate take office. This could be another reason for voter apathy at the municipal level.

But if higher voter turnout comes at the cost of implementing political parties at the local level, Mayor Watson says he’s not on board.

“As we’ve seen in other jurisdictions, along with those systems comes serious ethical issues when it comes to fundraising,” he said.

Issues around fundraising and party affiliations took place in Montreal recently, contributing to the city going through a handful of mayors in the past year and several local politicians facing accusations of taking kickbacks.

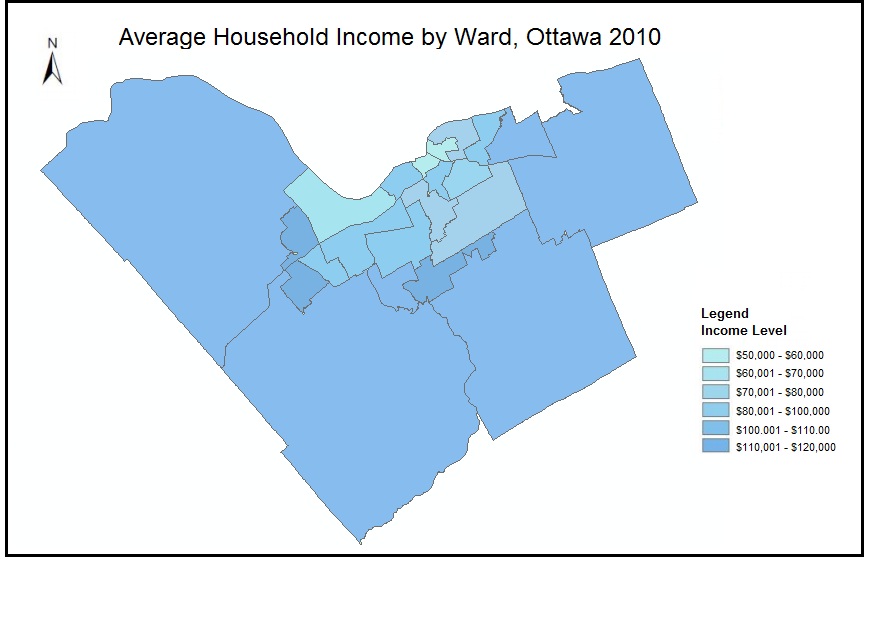

But the biggest factors in what persuades or dissuades someone to vote tend to be education and income. In the 2010 Ottawa municipal elections, Bay and Kitchissippi wards tied for the highest turnout rates, at 51 per cent. Respectively, the average household income in those wards is $67,000 and $84,000. On the other hand, Rideau-Vanier ward, which had the lowest turnout at just 39 per cent, has an average household income of $55,000, according to ward profiles available on the City of Ottawa website.

“Older, higher-income, full-time employed, working in white collar occupations and particularly those with a university or college education” are the people most likely to vote, says Walks.

Still, it may ultimately come around to a simple sense of civic responsibility.

“Most research has found that those who vote consistently feel they have a duty and responsibility to vote. Those that do not – particularly young people – report not feeling that sense of duty,” added Walks.

So do municipal politics even matter?

To that, Mayor Watson says that “as soon as you turn on a tap, walk on a sidewalk, or take a bus, you are using municipal services. It is in your best interest to engage with the municipal government to ensure your tax dollars are being well spent and you are being well represented.

Of course, it’s clear why the Mayor of Ottawa would say that. Still, municipal politics are where people can truly begin to engage and hold their elected officials to account. Councillors tend to be more accessible than, say, the local MP. Their decisions affect citizens most directly and most quickly. In that sense, despite a plethora of well-researched theories, the reason for low voter turnout at the municipal level remains puzzling.

-30-