The number of Canadians infected by bacteria spreading within hospital walls is increasing, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. Healthcare related infections are now the fourth leading cause of death in Canada with thousands of victims every year and it costs millions of dollars.

When you go to the hospital, it is to be cured. However, for 220,000 Canadians every year, it is not what happens. Staying at the hospital will get them sicker than ever.

These unlucky patients contract diseases triggered by bacteria multiplying inside medical institutions, also called nosocomial infections. On an annual basis, between 8,000 and 12,000 patients do not survive the infection.

“If you get a nosocomial infection, for sure, you need more treatments, more interventions,” explains Joanne Langley, professor of epidemiology at Dalhousie Medical School. “Each added illness increases the chances of things going wrong.”

On average, a patient having complications because of healthcare related infections stays 2.5 times longer in the hospital, a situation that costs more than $100 million per year for the healthcare system.

Numbers going up

“The natural tendency for these rates is to trend up incredibly,” says Virginia Roth, co-chair of the Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee.

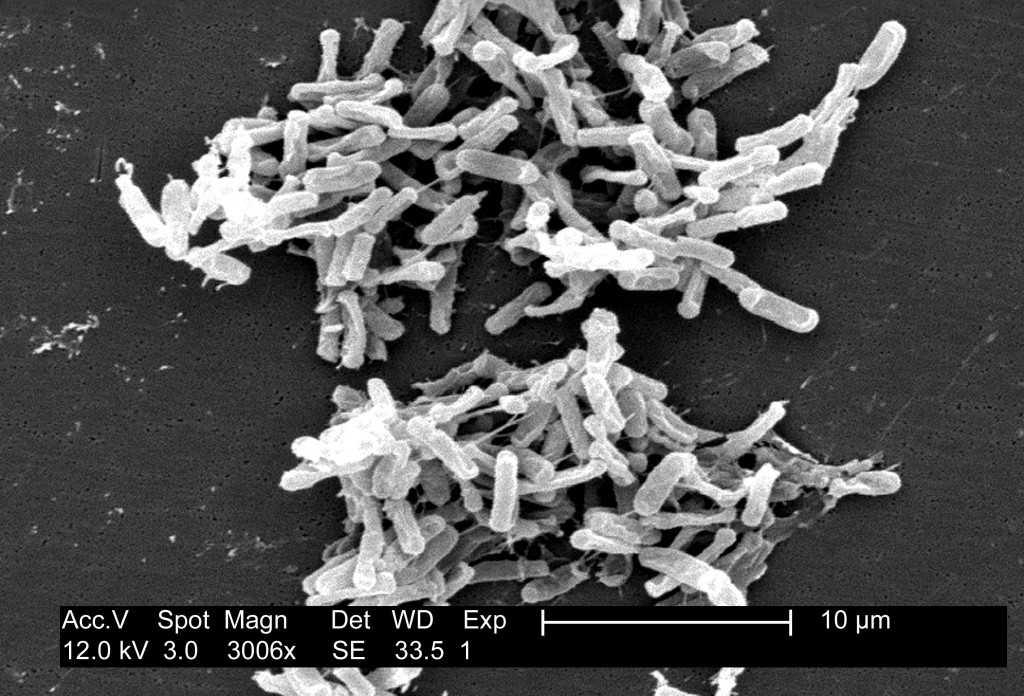

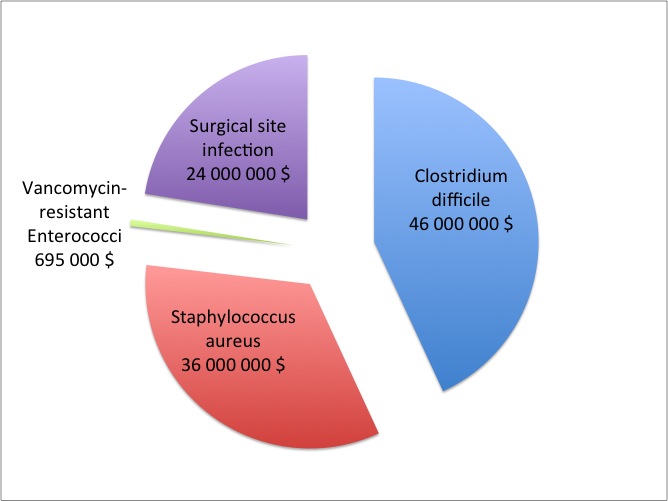

For example, the number of infections caused by Clostridium difficile was up by 6% in 2012, compared to six years earlier, according to the most up-to-date data from the Public Health Agency. In 2007, this bacterium, which spreads through contaminated feces in hospitals, killed 30 people. In 2012, the number went up to 49.

Medical authorities are also monitoring the Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium transmitted by skin-to-skin contact, mostly between healthcare workers and patients. “In 2012, there were 7,000 cases. That’s a lot of Canadians that are affected by this,” says Langley. The infection rate increased by more than 1,000% since 1995. More people are getting sick because of it, but more patients are also carrying it without having any symptoms.

While some of the infections are well known, others also emerge. It’s the case for VRE, acronym for Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci. This infectious microorganism lives in the human intestine. In 1999, only 10 cases where noticed. Since then, it is spreading exponentially. In 2012, 482 patients were affected by it and the Public Health Agency indicates that the data understates the gravity of the situation.

Multi-resistant bacteria

“Normally, we would treat VRE with vancomycin,” explains Langley. “But the bacterium acquired the ability to destroy this antibiotic. So that makes it a very difficult infection to treat now.”

Staphylococcus aureus also became a multi-resistant bacterium that complicates the work of doctors and threatens the life of patients. Moreover, it is a difficult microorganism to get rid off. It can survive on the floors for several days and even several months on fabrics.

For C. difficile, the situation is different: the microorganism is naturally resistant. When a patient is given antibiotics, the non-resistant bacteria present in his gut die, but not C. difficile. The bacterium then starts to multiply in dangerous proportions while producing toxins. It is also a very difficult bacterium to remove. C. difficile creates spores able to survive up to 5 months on surfaces such as tables or medical equipment.

What are the causes?

For the Canadian Union of Public Employees, it is very clear: there is not enough money attributed to the healthcare system. According to their reports, hospital beds were cut by 36% between 1998 and 2002. The data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows that there are now less than 3 beds per 1,000 citizens in the country. Canada is at the end of the organization list, just before China.

The Union claims that the bed cuts increased the hospitals occupancy over 90%, creating a favourable context for outbreaks. The Public Health Agency of Canada states itself that overcrowding is a risk factor for VRE.

Another cause: healthcare workers do not wash their hands enough. “Typically, hands hygiene rates, not only in Canada but globally are significantly low,” says Suzanne Rhodenizer Rose, President-Elect for Infection Prevention and Control Canada (IPAC). We verified the hand washing rates for Capital Health Hospital, in Halifax. The latest data available on the hospital’s website showed that hospital workers wash their hands just half of the time before a contact with a patient, even if it is one of the best ways to prevent infectious diseases to spread.

However, for Joanne Langley, washing your hands seems simple, but not in a context of financial constraints for provinces and, therefore, hospitals. “If the staff is more rushed or stressed, they tend to not fully comply with all the infection control measures, just because they are doing so much work and they are so busy. So with less staff, budget pressures can harm the ability to control infections for sure.”

The Canadian Union of Public Employees also claims that the budget cuts reduced the amount of money spent to clean hospitals, leading to a multiplication of dangerous bacteria inside the facilities.

A fight already lost?

According to the World Health Organization, it is possible to reduce the number of healthcare associated infections by half. However, for Dr. Roth, the reality is less optimistic: “We can’t control what’s outside our hospital walls. In other parts of the world, we see emergence of newly resistant organisms. They travel. We will see them at one point. So I am not sure we can be successful.”

One thing is certain though, “we should be more judicious in our use of antibiotics overall,” says Joanne Langley. “Overuse of antibiotics leads to resistance in bacteria and fewer solutions to treat them.”

With antibiotics used on humans, but also extensively on crops and cattle, the experts want to establish an antimicrobial stewardship in the years to come. “It is a high priority,” says Suzanne Rhodenizer Rose, from IPAC. Without it, the most common bacteria could become almost impossible to stop and the number of nosocomial infection victims could go up, without any existing treatment to save them.